Asfari ble dømt til fengsel pga en nøkkelring

Naama Asfari fikk fire måneder på grunn av en nøkkelring som viste det saharawiske flagget. Human Rights Watch reagerer.

Publisert 01. september 2009

I helgen skrev Støttekomiteen om den saharawiske menneskerettighetsaktivisten Naama Asfari som på ny har blitt arrestert og dømt av marokkanske myndigheter. Det var da ikke klart hva årsaken til dommen var.

Human Rights Watch sendte i går en protest mot arrestasjonen av og dommen mot Naama Asfari.

Det viser seg at han like før pågripelsen haddde endt i munnhuggeri med en politimann som krevde en nøkkelring fjernet. Nøkkelringens motiv var flagget til den Saharawiske Arabiske Demokratiske Republikk. Å bære slikt flagg i Vest-Sahara eller Marokko straffes normalt svært hardt.

Asfari sier han ble banket opp av politiet under pågripelsen. Men ingen undersøkelser av det påståtte politiovergrepet har blitt igangsatt. Derimot var det Asfari som ble dømt til fengsel.

Morocco: New Jail Term for Western Sahara Activist

Human Rights Watch.org, 31 August 2009

(Washington, DC) - The conviction and imprisonment of the Western Sahara human rights defender Naâma Asfari on August27, 2009, for "showing contempt toward a public agent" shows that Morocco continues to punish peaceful activists who show their support for independence for that region, Human Rights Watch said today. Asfari has been in detention since a stop at a police check point on August 14 outside the city of Tantan in southern Morocco escalated into a heated exchange of words, which Asfari says began when a police officer ordered him to remove a Western Sahara flag from his key chain.The Tantan Court of First Instance sentenced Asfari to four months in prison; a cousin who was with him during the incident, Ali Roubiou, 21, of Tantan, received a two-month suspended sentence.

It is Asfari's third conviction in three years. "Moroccan authorities keep finding new excuses to lock Asfari up, but it seems that what lies behind it all is his peaceful activismo on the Western Sahara," said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. In 2007, Asfari was given a two-month suspended sentence, and in 2008, he was sent to jail for two months, in both cases on criminal charges trials that seemed driven by the authorities' desire to punish him for his political activities.

Asfari is the Paris-based co-chair of the Committee for the Respect of Freedoms and Human Rights in Western Sahara (CORELSO). He frequently travels to Morocco and the Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, often accompanying foreign delegations seeking to learn about the situation of Sahrawis. He was on such a mission when arrested. Morocco laid claim to Western Sahara after Spain abandoned its control of the territory in 1975. Morocco has since exercised de facto sovereignty over the territory, although few countries have recognized its sovereignty de jure. A Sahrawi liberation movement known as the Polisario, and many Sahrawis, continue to press for a popular referendum to determine the region's future status, anoption Morocco once accepted but now opposes.

The city of Tantan is near to, but not part of, Western Sahara; its population includes many Sahrawis. In the August 14 episode, police stopped Asfari and Roubiou's car near the entrance to Tantan to check their papers. Asfari told Human Rights Watch that a policeman noticed on Asfari's keychain the flag of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) - an entity that Morocco does not recognize - and ordered him to remove "that thing." Asfari responded by suggesting that the policeman remove "that thing," pointing to the Moroccan flag on his uniform. An argument ensued, police reinforcements were called to the scene, and Asfari and Roubiou were placed under arrest.

Asfari contends that when arresting him, the police threw him on the ground, kicked him and broke his glasses. Roubiou alleges that the police beat Roubiou on his back. The court released Roubiou on August 16 pending his trial, but placed Asfari in pretrial detention. Roubiou told Human Rights Watch that he showed the bruises on his back from the beating to the prosecutor that day.

After his provisional release, he circulated photographs purporting toshow those bruises. He also testified about the beating at his trial 11 days later, although the bruises had healed by then. While Asfari was in police custody, they asked him to sign a written statement (procès verbal), purportedly containing his own words, in which Asfari admits to insulting and physically attacking police agents while resisting arrest. Asfari refused to sign the statement on the grounds that it did not reflect what he had said to the police.

He testified at his trial that it was the police who had physically assaulted him and not, as the written statement suggests, the other way around. The police's written version also omitted his explanation that the incident began with the officer's objection to the SADR flag on his keychain. Asfari also told Human Rights Watch that when the police returned his personal effects they had confiscated when arresting him, they gave him back everything except for the keychain bearing the SADR flag. The prosecutor charged Asfari with "showing contempt" toward and assaulting civil servants (articles 263 and 267, respectively, of the penal code).

At their trial, both Asfari and Roubiou proclaimed their innocence and insisted that neither of them had assaulted any policeman. Although Asfari refused to sign the statement drafted by the police, it was introduced as evidence at his trial. Further evidence came from four policemen who testified at the trial that Asfari had assaulted them physically and verbally. Since they testified as victims rather than as witnesses, the officers were not required to give sworn testimony. One produced a medical certificate stating that the injuries he sustained during the incident required 25 days of rest.

The court did not, as far as Human Rights Watch has been able to determine, open an investigation into the allegations, repeated by Asfari and Roubiou at the trial, that the police had assaulted them when placing them under arrest. Within 30 minutes after the three-hour trial, the Judie announced the guilty verdict and sentences. It is not known whether the two men were convicted on both charges; the written verdict has not yet been issued.

Both men have the right to appeal their convictions. In the meantime, Asfari remains in Tantan prison. The trial was conducted under heavy security, although foreign observers were able to attend. On the morning of the trial, police in Tantan intercepted several Sahrawi human rights activists who had traveled from El-Ayoun to attend the proceedings, detaining them for the entire day, then releasing them without charge. These included Brahim Dahhan, Brahim Sabbar,Mohamed Mayara, and Ahmed Sbaï, all of the Association of Sahrawi Victims of Grave Human Rights Violations; Saltana Khaya of the Forum for the Future of Sahrawi Women; and Bachir Khadda, Hassan Dah and Sidi Sbaï.

Asfari told Human Rights Watch today that police were openly monitoring the Tantan home of his father, where some of the foreign trial observers had spent the night. While there have been noted improvements in the protection of freedom of expression in Morocco over the last two decades, advocacy of independence for the disputed Western Sahara continues to be illegal. Sahrawi human rights activists sympathetic to the cause of independence are subject to police surveillance, harassment, and, on occasion, politically motivated prosecutions.

"There is no question that a traffic stop led to a sharp exchange of words," said Whitson. "But from the confrontation over a flag on a key chain to the hastily pronounced four-month prison term, the chain of events suggests that Naâma Asfari's pro-Sahrawi activism has led to his being in prison - yet again."

Nyheter

Bli medlem. Få plakat

Slik kan du bli medlem, og få verdens fineste plakat i posten.

12. februar 2026

Ny rapport: Sertifiserte folkerettsbrudd

Internasjonale sertifiseringsstandarder dekker over Marokkos kontroversielle handel med fiskeri- og landbruksprodukter fra okkupert Vest-Sahara, dokumenterer ny rapport.

16. desember 2025

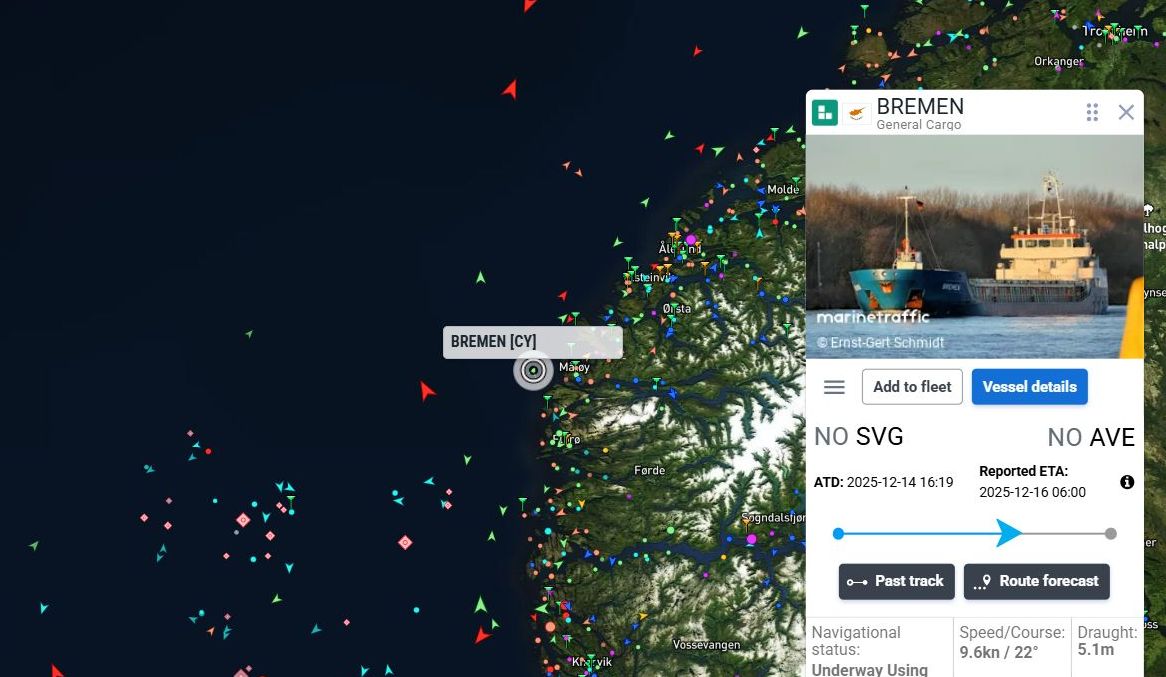

Nå: Skip ankommer Skretting på Averøy med last fra kontroversiell leverandør

Et fartøy med fiskemel ankommer i natt Averøy utenfor Kristiansund. Transporten åpner spørsmål om et hullete sertifiseringssystem.

15. desember 2025

Ny rapport: Marokko grønnvasker okkupasjonen av Vest-Sahara

En ny rapport beskriver de massive - og dypt problematiske - prosjektene for fornybar energi som Marokko utvikler i okkuperte Vest-Sahara.

11. desember 2025