One film festival in the world is different from all others. Read Asria Taleb's encounter with a festival audience in the Saharawi refugee camps in Algeria - including her connection with a complete stranger.

All pictures by Asria Mohamed, except the first picture taken by unknown photographer (contact asria@vest-sahara.no for proper credits).

By Asria Mohamed

Meeting her was like travelling back in time with a time machine. Twenty years ago, I had the same aspiration as her, but I had no one to relate to. I was happy to meet her, on my first trip home to the refugee camps where I am from. The film festival FiSahara in the sand dunes in the Saharawi refugee camps, makes people connect with strangers across generations and backgrounds. Here are 10 reasons why you should attend the most unique film festival to be experienced.

It is the people of the camps which make FiSahara unique

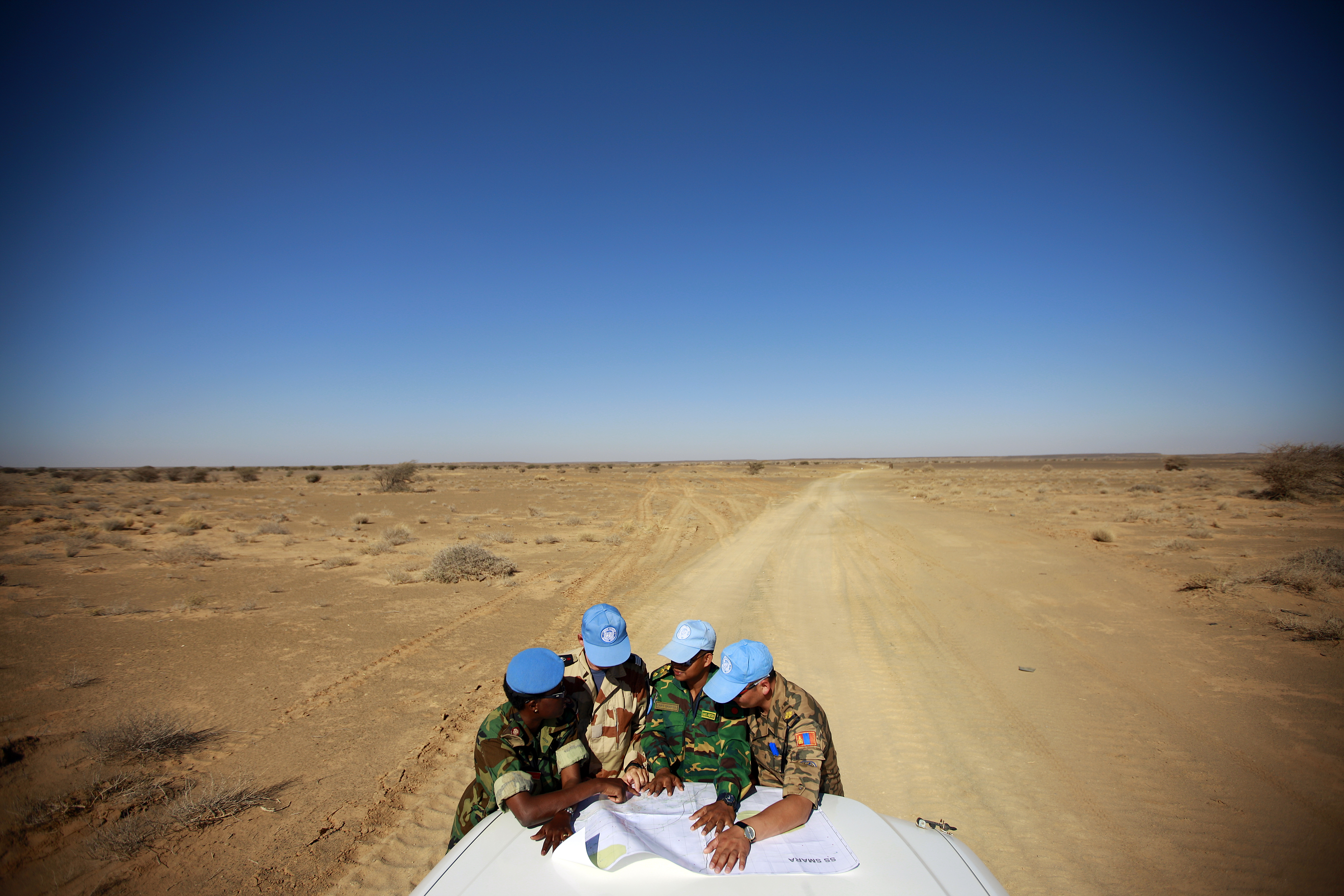

The type of the desert where the Saharawi refugee camps are located has little diversity in its landscape and the dry dust exhausts your soul before your lungs. Yet, you keep coming back only for one reason. The people. The Saharawi refugees. My people. They are the reason why this film festival survived, despite all odds, for 17 editions. They are the reason why foreigners from all corners of the world travel back again, and again. They are the reason why famous people like Itziar Ituño from the Netflix series ‘Money Heist’ this year visited the camps, just as the Spanish actor Javier Bardem did some years back. As Saharawi who is born, and raised in the Saharawi refugee camps, I am both proud, and impressed. As the Saharawi cinema school and FiSahara co-director, Tiba, said «This festival is a good example that there is nothing impossible for the Saharawi people»

Thrown into it

My participation at this year’s edition was more by accident. But what a fortunate one. I was in the camps together with my friend and colleague from Norway, Tone, to hold a workshop for women. The first day, I walked around observing from outside. It was on the second day that I got closer to behind the scene, as I got to experience watching films with local crowds. It was only after I was asked to help in the festival that I understood how much work the organisers put into it. I was given the job to co-host one of the evenings, presenting some of the films. The films that night were “Saharawi themed films” and “films made by Saharawis”. My job was to present the films and their production teams in Hassaniya and English, and to translate their speeches.

When you hear the engines of the trucks, the film is about to start

Long before the time of the screening, the audiences were sitting on the ground waiting patiently for what FiSahara has to offer. Now, what is missing is the cinema screen, and it is not your super modern, fancy European cinema room. It is a huge white truck, to which a large piece of wood has been glued to one of the sides. The truck drives few centimeters, and parks front of the curious audience.

FiSahara is inclusive. The dream almost 20 years ago of Saharawi creating films themselves is today a reality

At the venue where the festival is taking place, you would see young people wearing black vests. On it, it is written “Cinema school”. These people are either students or workers at the local film academy in the refugee camps. Some of these young students had themselves made a few of the films presented during the festival. In fact, my favorite films were those made by Saharawis. They were not only my favorite; they were all the viewers’ favorites. Why? The themes reflected ordinary refugees’ life.

When I was presenting each film, I called the production teams up to the stage. All of them were Saharawis. I was proud and shouted their names, while asking the crowd to give them a big applause. “Azza, Faragi, Mohamed Salem, Machoura, Zarga”. And the audiences didn’t disappoint. They received each one of them with same pride that I was feeling. The short films were the fruit of their studies in the cinema school.

FiSahara is authentic, and its authenticity comes from the audience

In Europe, people would check the cinema program. They would study the detailed reviews about film before they decide if they want to see it or not. The FiSahara audiences are much more flexible and open. It is not only about watching a film. It is more than that. It is about attending concerts, shows, workshop, and meet foreigners attending the festival.

Representation matters, and it seems that FiSahara takes that seriously

After presenting each part. I would go and sit with the crowd, on a carpet on the sand. Now I am not only having pain on my feet, but also on my back after 17 hours with high heels. (I love heels, and would wear them both on the icy roads in Norway or in the sand in the desert). This is when my high heels come handy. I lay down to minimize the discomfort in my back, using them as a head pillow. I placed my phone, the microphone and my notes next to me. I placed myself next to a group of girls. I did it on purpose. I wanted to spy on them, to hear their impressions about each movie.

The girls next to me saw that I was struggling to fix my pillow (my high heels). So one of them offered her thigh to support my head instead of my high heels, while the other one asked her friend to make more space for me. I am a very curious person, and love to give advice whether someone asks for them or not. For some it is inspiring for others maybe it is just annoying. “How many films are left?”, one young girl asked me. Most films were short, but the final one of the evening was almost an hour long. To be very honest, I did not want to say that as I was afraid they would leave. So I asked her "Do you have school tomorrow? What do you study? What you want to study? What is your favorite subject? Do you speak other languages?”. I bombed her with questions about her studies and dreams. I later realized that I didn’t even ask her about her name.

My own companions had all left. I was alone, but now I have my own gang, of nameless new friends. Our common thing is that even when life and injustice forced as to be refugees, we still have hope and determination in life.

My new friend, a 15-year-old secondary school student, was equally curious about me as I was about her. She also asked the same questions. I automatically took the role of the older sister. Starting with how important it is to pursue education. How, despite being a refugee with limited resources, she can make it and reach whatever dreams she wants. One of the local movies on the screen, Mutha, of a woman female landmine clearer, served as the best example.

Now we were in a deep conversation about my own journey as a female refugee Saharawi journalist, and her aspiration as a young girl in the last year of secondary school with a long life ahead of her. And I genuinely want to believe that she can do it. When I was her age, I did not have someone to identify myself with. I had so many heroines in my life but not in sense that I needed.

I was exhausted, and I could have just closed my eyes, or found a corner until next time I needed to enter the stage, but I was so inspired to speak to these girls. I was aware of my words and actions. I wanted this girl to be inspired to study, to pursue her dreams, to not be afraid to take place. I knew that it is easier for her to identify with me than many of the other foreign journalists, or participants on the festival.

The next day, I was walking, and I felt someone grabbing my melhfa. Guess who it was? It was her, my new sister. We hugged, and we said goodbye, but we still do not know each other’s names.

FiSahara reflects the refugees’ daily problems

I watched the “Imminent Danger” while sitting next to an old woman, and her daughter, both adults. I smiled hearing their reaction to a movie, to the point where I had a tear in my eyes. The old woman was so much into the events of the movie. She was so mad at the character, which sells drugs to kids in the camps. She was swearing at him, and wishing him everything bad in life. One could even get the impression that she believed that the characters in the film, and the film were real. Again, as the curious person I am, I asked them which film they liked best, and why. The answer was this film. They said because it is something that threaten our children, and it is a conversation that deserves to be addressed. I would have given Azza – the young and beautiful film director - a prize if I could. The movie was serious, funny, relatable. It was a mirror to a problem every parent and grandparent is worried about it. The remaining days, I kept stalking Azza, taking pictures with her.

FiSahara gives the Saharawis a platform

Saharawis are generally excluded from international platforms, whether they are political or cultural. Movies made by Saharawis would maybe never make it to any audience without the support from the FiSahara international film festival. It is amazing that films made by Saharawi refugees can be shown locally while reaching international audiences. Most people attending the festival are experts in their field. They are people with network in film-world. Some are known actors. This gives Saharawi young films’ creators a unique opportunity to be in direct contact with the right people in the field.

One of the filmmakers never needed help to present his film in English. He could do that well himself. “The Nomad Garden” is directed by a polite young man with a warm smile, Mohamed Salem Mohamed Ali. He was humble despite winning the third place. When I asked if I could take his picture, he held his prize down trying not to make a big fuss out of it. Well, you bet I did not leave until I made sure he held it up high because he earned that prize as much as the international filmmakers.

FiSahara celebrates the whole Saharawi culture

Living in Norway, the sunset is magic, a daily experience that lasts for hours. In the camps, it is beyond magic, but it takes shorter time. The scene of the light of the sunset over the black Saharawi traditional camps make you forget that you are in a refugee camp. It is so romantic that you for a second might feel you are in an expensive resort. That is precisely what is unique about the camps, and Saharawis. Their ability to transform the inhospitable ‘hamada’ to heaven.

Lefrig - a traditional exhibition of Saharawi culture - is what the FiSahara film festival offers for example when you get bored of workshop or film. You can walk around these tents and experience the Saharawi culture. You can listen to poetry. You can play Saharawi drums or Saharawi traditional games. You can do your best to take part in the local dances, and people would cheer for you.

Tone and I were done with our workshop, and early for the next event, we walked around the tents and I felt so proud sharing my culture with her. Translating Saharawi poetry. Showing her how I learned my first sentences of the Quran.

FiSahara brings you close to the refugees, and their daily life: you sleep at their homes

If you join FiSahara you spend the days with Saharawi families. Your wake-up alarm is the sound of the famous Saharawi tea. The families would place everything they own to your disposal. They have fewer possessions than what people have in Europe, but it feels that they are way richer. They are not only generous with their gifts, time, house but also with their attention, curiosity, love. Every day when you return, they are standing there with big smiles. They asked about how your day went, and they genuinely wish to hear the answer. The family that I had the pleasure to spend some nights with in the Awserd camp, had more cats than children. At some point it felt that the cats were also guests because every time the food were served, they stood around the table waiting for us humans to share with them. One in my group was chasing them away. The family did not.

Their three daughters were on their feet the whole day making all three meals and tea, and making sure everything was clean and in place. For a European, this might not sound challenging. But it is when do not have a running water. One has to physically carry water buckets both to the kitchen and to the bathroom. Last day, when I said goodbye to the host family, their daughter ran after me bringing me a gift. It is Saharawi tradition that you never show up empty handed, and you will never leave without something. I was so ashamed for showing up, and without leaving something behind. I had forgotten.

FiSahara heroes are its organizers

The time had passed midnight. Maria and I were done presenting. It was time to pick up the heavy backpack with recording material and go home. I forgot that I hadn’t eaten all day until Maria asked if I want to eat. Do you want to guess where we were going to eat? In a truck!

One of the FiSahara volunteers helped me into the vehicle, where the beaming projector is installed. Everything behind it is darker except the big smiles, and spirits of FiSahara festival workers. Inside the truck, there was a messy table with a big cooking pot of spaghetti, yoghurts and some cookies. It seems most people had eaten except Maria, the festival co-director who generously shared with me. You know what I am most surprised with such people? They actually find time to eat. Maria, Mayka, Sara, David, Gon and so many others that I didn’t had chance to speak with had so much to do. They were running everywhere. Yet, with their walkie-talkies they managed to look so chill, and relaxed. They were calm, collected, professional, even under pressure. Despite how super busy Sara or Maria or the others were, they still had time to answer whatever type question you had. They seemed well-coordinated, strong and showed so much respect to the local organizers.

The real heroes are the Saharawi organizers

Most of duties and responsibilities lay on Saharawis as both the host, and the organizers of the festival. This means the pressure is even harder on Saharawis, starting from hosting logistics to making sure that the camel - which is the prize of the winner of the festival – has arrived to the location. And everyone, Saharawis and internationals, come to Tiba for help. If the international team looked calm. Tiba seems happily calm, with smile on his face whenever your paths cross.

FiSahara is for everyone including children:

I would never erase this image from my mind. The child is so amazed of the clown show, totally enchanted. Most of the audience were children. You could notice that they are bored when adults speak. But when the clown show started, all of a sudden, they all stood up, pushing each other and us sitting in the front row in order to get a spot where they can see the whole act, mesmerized. At this point, I get easily angry – at the world and Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara. And the international community that stole from them the opportunity to feel amazed more often than they can in the setting that they live in.

Saharawi media and Saharawi security

I worked as a journalist in the Saharawi refugee camps. I know how challenging it is to work with limited resources, yet, these people manage to deliver. These two people in the picture are there all the time, filming from the ceiling of the building next door or from underneath the white truck, and running up and down the crowds sitting in the sand dunes. When I interviewed the co-founder of the local media group Saharawi Voice, Mohamedsalem, he said something that stuck in my mind. “No matter how sympathetic you are to the Saharawi cause, you can never tell the Saharawi story the same way as a Saharawi”.

Some foreigners are afraid to travel to the camps and some governments advise against traveling to that part of Algeria. So I wanted to dedicate the last words to the Saharawi police, and security forces for being there constantly even though there is no apparent reason for their presence.

You have a dream to walk the carpet of fame. Book your tickets for next edition

I brought my red shoes to walk on the carpet. I end up forgetting them in the car. Here walking on the carpet with my sport shoes. Sharing laughter, and making silly faces with friends. You know who walked this carpet too: one of the stars of ‘Money Heist’. FiSahara gives you chance to meet all types of people. It is indeed what art and culture is about. It brings people together.

See you there next year!

Order our Western Sahara poster!

“Try to Visit Western Sahara”…

The Security Council fails Western Sahara and international law

On 31 October 2025, a new resolution was adopted in the UN Security Council calling on the Saharawis to negotiate a solution that would entail their incorporation into the occupying power, Morocco.

Saharawis Demonstrate Against Trump Proposal

The United States has proposed in a meeting of the UN Security Council on Thursday that the occupied Western Sahara be incorporated into Morocco.

Skretting Turkey misled about sustainability

Dutch-Norwegian fish feed giant admits using conflict fishmeal from occupied Western Sahara. Last month, it removed a fake sustainability claim from its website.