We have talked to human rights activist Mahfouda, who recently was sentenced to six months in a Moroccan prison for reprimanding a judge.

Photo: @ElliLorz

On November 16, 2019, the Sahrawi human rights activist Mahfouda Bamba was sentenced to six months in prison. Mahfouda has been active in defending the rights of her people since 2005. Over the years, the 37 year-old mother of two has been subjected to a number of reprisals by the authorities, who have wished to silence her. She has been physically harassed, her salary has been reduced, she is threatened with sexual violence, and her husband has lost his driver’s license.

This week, The Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara spoke to her on the phone about what has been the most violent response from Moroccan authorities so far.

She explains:

It happened during the trial of my cousin Mansour. There was a break during the procedure, and my cousin’s mother – my aunt – asked if it was ok to go outside to get some air. But then the judge yelled at my aunt for talking loudly in the courtroom. I could not believe that he could be so disrespectful. “Show respect, she is your mother’s age. Show her respect”, I told the judge.

Without further explanation, I was taken to the prosecutor’s office, and then to the police station. I was ordered to dress naked. They hit me on my back. The police took my phone, wrote down everything they could, and studied who I had called. They accused me of asking people to come to the courtroom.

I spent all night at the police station, on an old and smelly mattress. The cell was dirty, with cockroaches. I was the only woman there. I had no idea why I was there or what was going to happen to me. I was not given anything to eat or drink.

The next day I was returned to the courtroom. I had no defender, and no one in my family was present. The prosecutor asked me questions, and a man took notes. I was forced to sign documents with my fingerprint, without knowing what was written on them.

No one else was allowed to enter the courtroom. My husband and my brothers stood on top of a rock outside the building to try to see what was happening through a closed window.

The police had taken both my phone and my sunglasses, and they handcuffed me. I was taken to a cell in the courtroom. I still had no idea what they meant I had done. I asked a policeman if he knew. The only answer he gave me was that he was frustrated because he had to work during the weekend. “Because of you, I had to work on a Saturday”, he said.

Outside, my family asked another policeman what was happening to me. He replied that if a police car now came to the courthouse, I would be taken to jail. I was told that my brother reacted hysterically when the police car arrived. “You cannot take her there”, he shouted. He had spent time in prison himself and knew well what it was like there.

I was led out of the courtroom, handcuffed. Then I heard the voice of my husband shouting “be strong, Mahfouda”. Then I was taken into a police car. The windows were dark. I still had no idea what was going to happen to me, or where I was going.

I arrived at the prison. The administration was there, waiting for me. It was like a nightmare, and I had no idea that the story would take this direction. I had not had anything to eat in a day, so as soon as I arrived, I fainted and hit my head against a flowerpot made of cement. They did not check my head but gave me a paracetamol.

I was to spend six months in jail.

I shared the cell with eight other women. I was the only human rights activist; the others were convicted for various crimes. The others slept on beds. I was given a blanket and was directed to the floor. The cell was two meters in one direction and three meters in the other.

There was a toilet in the corner of the cell, with a kind of half of a door that was forbidden to close. There was no ventilation in the cell. Drops of water sometimes settled on the cell walls because of the humidity, and caterpillars kept crawling up from the toilet holes. The stench was unbearable, especially at night.

Every morning we were awakened by the sound of metal, as the guards knocked on the door very hard. Everyone had to get up and stand, and they counted us. The first few days I fainted. I woke up in shock every morning from the brutal way they woke us up.

The food was horrible. It was not uncommon to find cockroaches or insects in it. Those who had money could buy some canned food from the prison shop, so we survived mostly on canned food. We had to be outdoors from one o’clock until four o’clock in the afternoon – during the cold winter this was unbearable.

They forbade me to have books, notebooks, or pens. I still managed to get hold of a pen and a piece of paper, which I hid in the cell. That way I was able to write some sort of a defense speech for myself. But the other prisoners spied on me on behalf of the prison administration. It was not long before I was called to explain myself to the administration. The boss was red in the face with anger. He accused me of provoking the other prisoners to protest against the prison.

Throughout my stay, I was harassed and provoked by the other prisoners. I once found fingernails in my food.

Everything got worse with covid. Still, they did nothing about the hygiene conditions. We never fully understood the extent of the pandemic or what it really was about. I remember I was afraid of what it really was, and that I might never would be able to see my family again. Suddenly, visits were no longer allowed.

On Mondays and Fridays, I was allowed to call my parents and my husband for five minutes. A guard was always near me, so they would know what I was talking about. During weekends, I always thought about how people on the outside had days off. On the inside, the days went slowly, very slowly.

I used to think about how I ended up in the situation I now was in. I had always been interested in the occupation of Western Sahara, and the situation of the Sahrawi people. I have always been aware that half of my people – and half of my family – were thrown into exile. Back in the old days, we used to exchange audio recordings on cassettes that family members recorded for each other. My real activism started in 2005, when a Sahrawi youth in my town was killed by the Moroccan police. At that time, my oldest daughter was two years old. I made by husband promise that he would never tell the rest of the family that I had taken to the streets to demonstrate.

He is still supportive of me. In prison, my husband used to visit. He had the children with him. Each visit was emotionally very hard, for all of us. The children used to cry while they hugged me. My son always told me he would give me one kiss for Saturday, and one for Sunday. Once I saw my son staring blankly in the direction of the prison guards. I realized he was afraid something might happen to me. I looked him in the eyes and said “You know, these guards? Mom can easily beat them up”. He smiled and we continued our conversation.

I was never allowed to get more than four visitors at a time. My family used to show up at eleven o’clock, and after a few hours of waiting, they saw me at three o’clock in the afternoon. They were always searched. We were ordered to speak loudly, and we were forbidden to whisper in each other’s ears. Three guards always followed what we said.

It is absurd that I had to go through all this – for my little comment in the courtroom. If the judge felt offended, he could have told me, and he could have asked me to come to his office to apologize. Instead, they imprisoned me to send a message to other female activists.

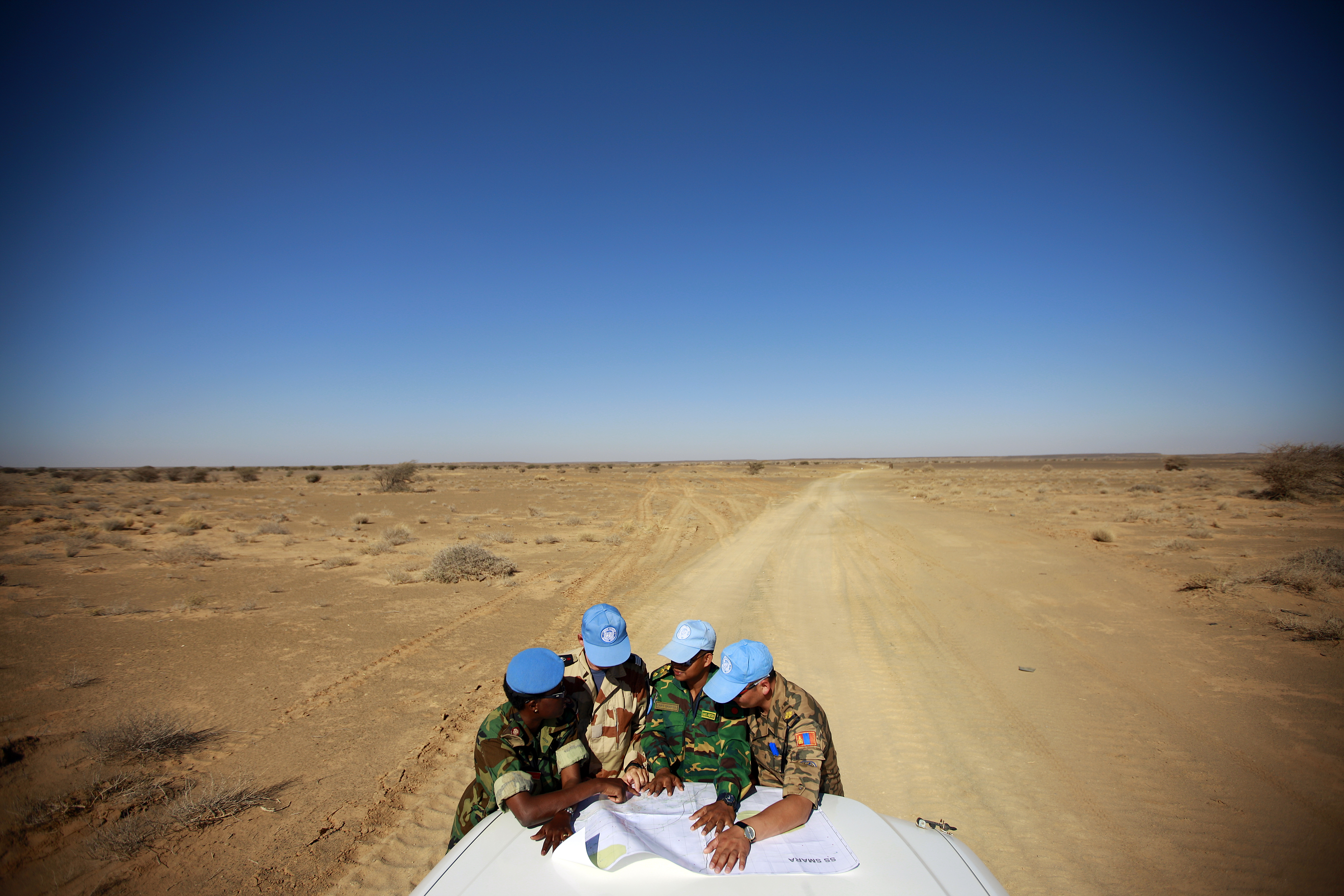

What I think about the UN? Well, the MINURSO operation has never had a real effect on our situation here in Western Sahara. They have not implemented the referendum, and they are not allowed to report on the daily violations that take place here.

Order our Western Sahara poster!

“Try to Visit Western Sahara”…

The Security Council fails Western Sahara and international law

On 31 October 2025, a new resolution was adopted in the UN Security Council calling on the Saharawis to negotiate a solution that would entail their incorporation into the occupying power, Morocco.

Saharawis Demonstrate Against Trump Proposal

The United States has proposed in a meeting of the UN Security Council on Thursday that the occupied Western Sahara be incorporated into Morocco.

Skretting Turkey misled about sustainability

Dutch-Norwegian fish feed giant admits using conflict fishmeal from occupied Western Sahara. Last month, it removed a fake sustainability claim from its website.