"The Gdeim Izik events in October 2020 until the Guerguerat demonstration in 2020 can be read as a sign of the UN's lack of orientation", writes Saharawi political prisoner Naama Asfari from his prison cell.

The Saharawi political prisoner Naama Asfari is this month completing the first 10 years of a 30 years sentence in a jail in Kénitra, Morocco. Asfari is co-president of a human rights group defending self-determination in Western Sahara, and was detained on 7 November 2010, the day before the Moroccan government dismantlement of the so-called Gdeim Izik protest camp in 2010.

7 years later, he was sentenced for something he is said to have done the day after he was imprisoned. The sentence was based on confessions he gave under torture. In 2016, the Committee Against Torture held that Asfari had been tortured and that Morocco had refrained from investigating it, with confessions signed under torture being used against him.

The Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara has received the text below, authored by Asfari while in jail. The text was scribbled by Asfari on paper and read up through the public prison phone and transmitted via his wife in France.

"Gdeim Izik : The right to anger.

The Anger which allows us to set the limits of the conflict

From the prison of Kenitra, Morocco, 28 October 2020.

In a celebrated passage of The Phenomenology of Spirit, which is the dialectic of master and servant, Hegel describes the conflict between two individuals leading to the enslavement of the weakest. I first see the other as a threat to my identity. A struggle to the death is then engaged for recognition at the end of which the dominated one acknowledges the superiority of the dominating one. But this relationship is not set or fixed.

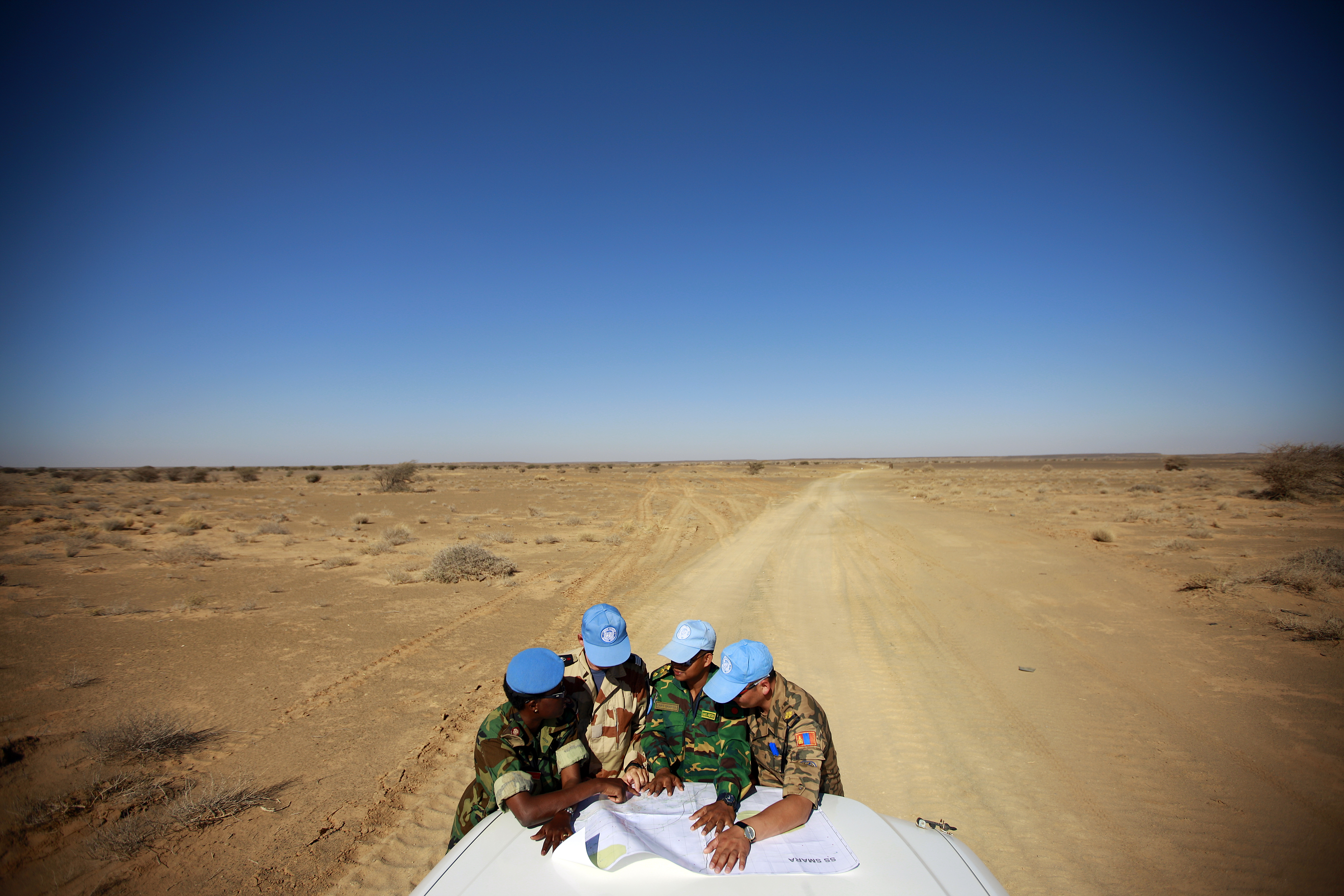

The dominating one actually needs the dominated in order to be recognised as master. In this sense he is not autonomous. The dominated one accedes for his part to the recognition of himself through his work which allows him to fashion his identity, denied initially by the dominating one. Today, we can decipher the struggle of the Saharawi people in the Occupied Territories in this light. We can read through the prism of this dialectic of the dominant/dominated the Saharawi resistance movement, and throw light on the Gdeim Izik event of 2010, a historic moment in the peaceful combat of the Saharawi people. Why does Gdeim Izik express the anger of a people? Anger, repressed these last three decades of “no peace no war” returns to the foreground today with what has been happening at Guerguerat since 20 October 2020, a peaceful demonstration organised by civilians coming from the Saharawi refugee camps in Tindouf and the liberated Territories to celebrate Gdeim Izik and contest the negative presence of MINURSO – the UN Mission for the Organisation of the Referendum of Self-Determination for Western Sahara.

In order to understand all this, just read “Anger and Time”, an essay by the German philosopher, Peter Sloterdijk, published in 2006, which reads like a prophecy, which will become a classic of political philosophy. According to Sloterdijk, anger is the principal motive force of history. “It is the most widely shared thing in the world”, the author makes of the thymos, a concept invented by Plato to designate a part of the soul linked both to the emotions and to the social functioning of the individual, the heart of actions in political life. How can we find within passive anger an active, constructive anger? This is the complex spring which tries for good or evil to action movements and political parties, as Peter Sloterdijk explains.

The mythological hero Achilles is the first incarnation of this boiling anger, unforeseeable and therefore dangerous. This is why the question of its orientation is crucial. Just as there are banks where we can deposit our money, there are some where we deposit our anger while we wait for it to bear fruit: it is thus that the modern era can grasp a millennial emotion, according to the original reading that Sloterdijk makes of it. What is this emotional bank like in the Saharawi case? An occupation? To the status quo imposed since 1991 by the UN, with the hope of organising a referendum of self-determination, the means of making real the legitimate claim of a people, the fruit of the struggle for freedom and independence? Does the UN not promise the Saharawis to implement its agenda for the referendum and to defend the interest and the right of the Saharawi people to self-determination? The UN is even a sort of “anger bank” in so far as it claims to defend the interests of the people across the whole world. This reading which Sloterdijk calls “thymotic”, that is centred on the emotions, was very enlightening for me, it allowed me essentially to make of the UN an “anger bank” in which the Saharawis have deposited their “claim capital” in order to see it bear fruit. Today, discredited, the UN hardly plays its role of a channel. The events since Gdeim Izik in October 2010 until the demonstration of Guerguerat in October 2020 can be read as a symptom of the lack of orientation of the UN. One can thus consider the UN as a kleptomaniac stealing from the victim, deserving of his right, in order to give it to his aggressor. The Saharawis are concerned about the mood in the UN for the last 20 years which incites one to consider the Saharawi question of “settling a difference” and not as a conflict of occupation and self-determination. Until 1991 the question was framed in other terms. Today they speak of “settling a difference” as if there were no longer an occupation, nor on the United Nations level a referendum of self-determination. Only the Saharawi people are the big loser in such a situation. By giving the aggressor and the aggressed equal footing the UN creates a highly inflammable situation. Because implementing the UN plan beginning in 1991, is to receive a full and complete status which does not stop the occupation, nor the exploitation of natural wealth but can give sense to the presence of the UN. Being the loser is a humiliation. What is the most spontaneous reaction to losing? Anger!

“All losers do not let themselves be calmed down by pointing out the fact that their status corresponds to their place in a competition. Many will reply that they have never had the least chance of participating in the game and then to get classified. Their rancour is not so much about the winners but also about the rules of the game, which the loser who loses too often questions in a violent manner which reveals the critical case of politics after the end of hope”. This is how Sloterdijk concludes his reasoning on the anger of losers.

For Saharawis Gdeim Izik is the most beautiful, wholesome and just anger because it revealed the defects of the UN order. The first verse of the Illiad is: “Muse, sing me the anger of Achilles”. The anger of Achilles is initially the incarnation of law. This relationship with justice explains, for example in Aristotle, a conception of “healthy anger” which is not at all a stranger to the virtue of the golden mean. But the anger which aims at the reestablishment of law can overtake the law. With anger there is no resolution, just arrangements, provisional suspensions. The sublime final scene of the Iliad between Achilles and Priam is not a reconciliation. They look at each other “in silence, in the light of the moon”, Achilles says to Priam: “do not tarry” because the sun is about to rise, war will resume. The reestablishment of order happens face to face, in mutual recognition. The one living under occupation knows what it is to feel the pressure of the “no”. One can criticise sterile anger of the good soul or nihilistic temptations. And yet anger, contesting, indignation, revolt, refusal, the “no”, all these forms, more or less passionate in their negativity are also a way of not accepting the world as it is, of wanting it otherwise. I make no apology for the “no”, less still for anger, but I would like to rehabilitate the political and existential importance of belief in the possible.

“We are a freedom who choses, but we do not choose freedom: we are condemned to freedom”. It is around this paradox that the master work of the father of existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre articulates his thesis. The paradoxical charm of freedom, the thesis of Being and Nothingness today reflects our situation, we, the Saharawis.

Naâma Asfari"

Order our Western Sahara poster!

“Try to Visit Western Sahara”…

The Security Council fails Western Sahara and international law

On 31 October 2025, a new resolution was adopted in the UN Security Council calling on the Saharawis to negotiate a solution that would entail their incorporation into the occupying power, Morocco.

Saharawis Demonstrate Against Trump Proposal

The United States has proposed in a meeting of the UN Security Council on Thursday that the occupied Western Sahara be incorporated into Morocco.

Skretting Turkey misled about sustainability

Dutch-Norwegian fish feed giant admits using conflict fishmeal from occupied Western Sahara. Last month, it removed a fake sustainability claim from its website.