In occupied Western Sahara, Moroccan police confiscate the phones of female journalists and activists in search of images that could damage their reputations. In late November, new acts of war erupted after 29 years of ceasefire—alongside severe abuse of journalists.

Written by Asria Mohamed, originally published on the website of Norwegian Council for Africa.

In ordinary rule-of-law states, police often seize personal belongings as part of an investigation - with legal justification. In occupied Western Sahara, where war broke out again in November, the trend is different. Sahrawi activists and journalists are stripped of personal phones and laptops by police, only to discover that the content later surfaces, distorted and manipulated, on websites and social media. This practice particularly targets women, the bearers of their families’ honor.

PHOTO: Private

In 2018, young journalist Nazha El-Khalidi used her smartphone to livestream a street demonstration on Facebook. In the video, we see El-Khalidi shouting against oppression, followed by the feet of a police officer chasing her down the street. She was arrested and charged for presenting herself as a journalist without meeting the requirements set by Moroccan authorities. The penalty could have been two years in prison. After the UN Human Rights Council intervened and asked Morocco to drop the charges, she was fined 4,000 dirhams (approx. 3,900 NOK):

“I refuse to pay the amount. If I do, it means I agree with the complaint that criminalizes my work as a journalist,” says El-Khalidi, who spent one year studying photography at a Norwegian folk high school.

Moroccan police still have her phone. They have held it since her four-hour-long interrogation in 2018. Police have yet to explain why they’ve kept it. In 2016, authorities also arrested El-Khalidi when she covered a women’s demonstration in El Aaiún. She was held overnight and had her camera and memory card confiscated, none of which she has recovered.

After her phone was taken in 2018, El-Khalidi says police began spreading false rumors about her. They published private photos she would never have shared publicly and manipulated chat conversations with male friends and colleagues.

Content as a Pressure Tool

Her attempts to retrieve her equipment have been met with head-shaking at the police station. Based on conversations from her phone, police created stories suggesting she had sexual relationships. In the summer of 2020, new articles about her private life were published, using the most degrading terms to describe her. The articles remain online.

On November 21, she married her colleague Ahmed Ettanji, head of the media organization she is also part of. She says police interrupted the wedding by cutting the electricity in the neighborhood, blocking the doors to both her and Ahmed’s homes, and preventing guests from entering or leaving the celebration venue.

Morocco’s illegal occupation of Western Sahara is one of the least covered conflicts in international media. There are several reasons for this. One is the complete lack of political freedom in the territory. Parties, organizations, demonstrations, and newspapers that call for self-determination are banned or obstructed. The organization Freedom House ranks the territory as one of the least free in the world. Over 130 Norwegians have been denied entry to Western Sahara in the past five years, and Norwegian journalists are not granted press permits to travel to Morocco if their destination is Western Sahara. Authorities regularly obstruct Sahrawis attempting to travel abroad. Half of Western Sahara’s population has fled since Morocco annexed the land in 1975. Morocco views the territory as part of its kingdom. Protesting this is seen as a threat to Morocco’s "territorial integrity." The legal framework means that Sahrawis who speak out about their homeland’s future automatically risk imprisonment:

“Reporting independently from Western Sahara is considered a crime by the Moroccan regime. Insisting on doing so is my way of challenging the authorities,” says Sahrawi journalist Hayat Rguibi.

Human rights defenders, students, and journalists are subjected to harassment and punishment. Many are currently serving prison sentences of ten years to life. One of them is media activist Khatry Dadah, sentenced this year to 20 years in prison, ikely because Morocco believes he filmed a video of Moroccan police beating another Sahrawi journalist and blogger, Waleed Al-Batal, who is also in prison.

In late November, new fighting erupted after 29 years of ceasefire, triggering further serious abuses against journalists.

In this difficult situation, young women are trying to challenge the authorities. Simple Google searches show women are overrepresented in street protests. Sahrawi women face violence and abuse, especially those who report on it. Doing journalism in such a closed society is highly challenging. Sahrawi journalists cannot obtain information from courts or access indictments against political prisoners. They cannot go to the harbor to photograph ships extracting resources from Western Sahara or identify international companies that illegally purchase minerals from Moroccan state companies:

“How can we do investigative journalism? How can we report how much fish is taken from Western Sahara if we can’t speak to these companies? If we find someone willing to leak information, we put their lives at risk,” says El-Khalidi, who has worked continuously in photography since returning from school in Norway:

“Our work as journalists didn’t come from a long education or childhood dreams. We were forced into this out of necessity. We had to do it because there’s a complete absence of international media here,” she explains.

Technology as both a blessing and a curse

Young journalists explain that technology in Western Sahara is both a blessing and a curse. Thanks to social media, information about Western Sahara can reach the world. Sahrawi journalists and activists communicate globally through their personal social media accounts.

At the same time, technology enables Moroccan authorities to control them. Authorities hack accounts or steal equipment, then misuse the obtained information. Content is manipulated and published through fake or anonymous accounts, pitting families and activists against each other.

This pressure also exists in Morocco. On June 22, Amnesty International revealed that Morocco had used advanced spyware to infect the phone of critical Moroccan journalist Omar Radi. In both Morocco and Western Sahara, anonymous gossip sites support government narratives through fabricated stories. On July 16, a group of 110 journalists urged the Moroccan government to shut down this “defamation media” ecosystem.

In Sahrawi society, people tend to have a relatively relaxed relationship with religion. Western Sahara is often considered more gender-equal than other Muslim societies in North Africa and the Middle East. While this is partially true, it is still a traditional society with expectations women must meet. For instance, women are expected to wear the traditional Sahrawi dress, the melhfa, in public. Like other regional societies, premarital relationships, especially for women, are heavily stigmatized.

In addition to publishing content from confiscated devices, women often face hacking or surveillance. The content, usually fabricated or distorted, is published through fake accounts or anonymous gossip websites. Damaging a woman’s reputation or honor can make it difficult for her to work under the Moroccan occupation or maintain standing in her community. Being labeled immoral can result in local distrust - even among one’s own:

“Technology has fueled sophisticated disinformation campaigns. They use phone content to pressure us and harm our mental health,” says journalist Salha Boutanguiza, one of the first women to publicly condemn defamation. Boutanguiza produces news stories for the Sahrawi national exile TV station operating from refugee camps in Algeria.

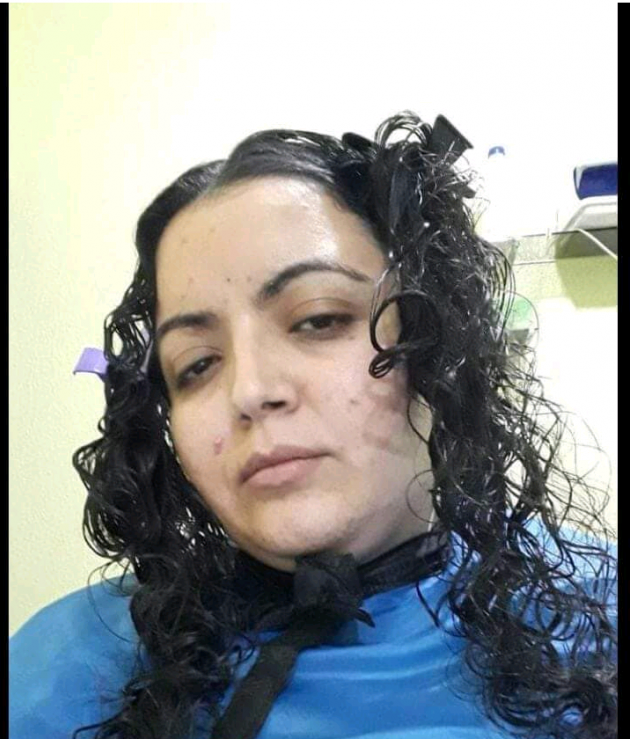

A Muslim, Boutanguiza usually covers her hair. Shortly after police seized her phone, a website and an anonymous social media account published a photo she had taken at a hair salon.

The image may seem innocent from a Western perspective but was a serious violation of her privacy. It was posted alongside claims that she was in a relationship.

Sahrawi female activists explain that their roles as guardians of family honor are systematically exploited by the authorities.

Monitored with their own cameras

Hayat Eguibi is one of the founders of Equipe Media, one of the most active media groups in the occupied part of Western Sahara, established in 2009. Eguibi began her activism in middle school, but her family didn’t know until she was arrested one night and had to stay at the police station.

In eighth grade, the school suspended her for 15 days. In ninth grade, she was no longer allowed to attend regular classes. Instead, she had to sit alone in a separate room the entire school year.

She has been barred from traveling abroad five times. In 2010, on her way to an international youth forum, she was arrested at the airport for participating in local protests in Western Sahara:

“The wall in the interrogation room was covered in bloodstains. Fresh blood. Anyone would be scared at that moment. I was before they brought me in, but the fear disappeared when I saw that wall. I knew it was my friends’ blood—they had been tortured. Instead of fear, I felt rage, and I repeated slogans for freedom and self-determination,” says Eguibi.

“I’m a journalist and activist who was accused of forming a terrorist group and carrying weapons. During the interrogation, they demanded I sign these claims. Every time we refused, they beat us again and hit us in the face

“I am a journalist and activist who was accused of forming a terrorist group and of carrying weapons. During the interrogation, I was asked to sign a statement admitting to these accusations. Each time we refused, we were beaten again and struck in the face while blindfolded. In prison, I was assigned cleaning duties. I refused because I am not a criminal, I was convicted based on my political beliefs. I began a hunger strike. Unlike everyone else, we were denied family visits for a month. They denied us everything, even pen and paper”, she says.

Today, Erguibi is temporarily released, which means the authorities still hold leverage they can use to pressure her. In the meantime, she and her colleagues are under surveillance using cameras that her own media organization had stolen by the police.

The Security Council fails Western Sahara and international law

On 31 October 2025, a new resolution was adopted in the UN Security Council calling on the Saharawis to negotiate a solution that would entail their incorporation into the occupying power, Morocco.

Saharawis Demonstrate Against Trump Proposal

The United States has proposed in a meeting of the UN Security Council on Thursday that the occupied Western Sahara be incorporated into Morocco.

Skretting Turkey misled about sustainability

Dutch-Norwegian fish feed giant admits using conflict fishmeal from occupied Western Sahara. Last month, it removed a fake sustainability claim from its website.

Morocco plans massive AI center in occupied Western Sahara

A 500 MW hyperscale data center for Artificial Intelligence is being envisaged in the occupied territory.