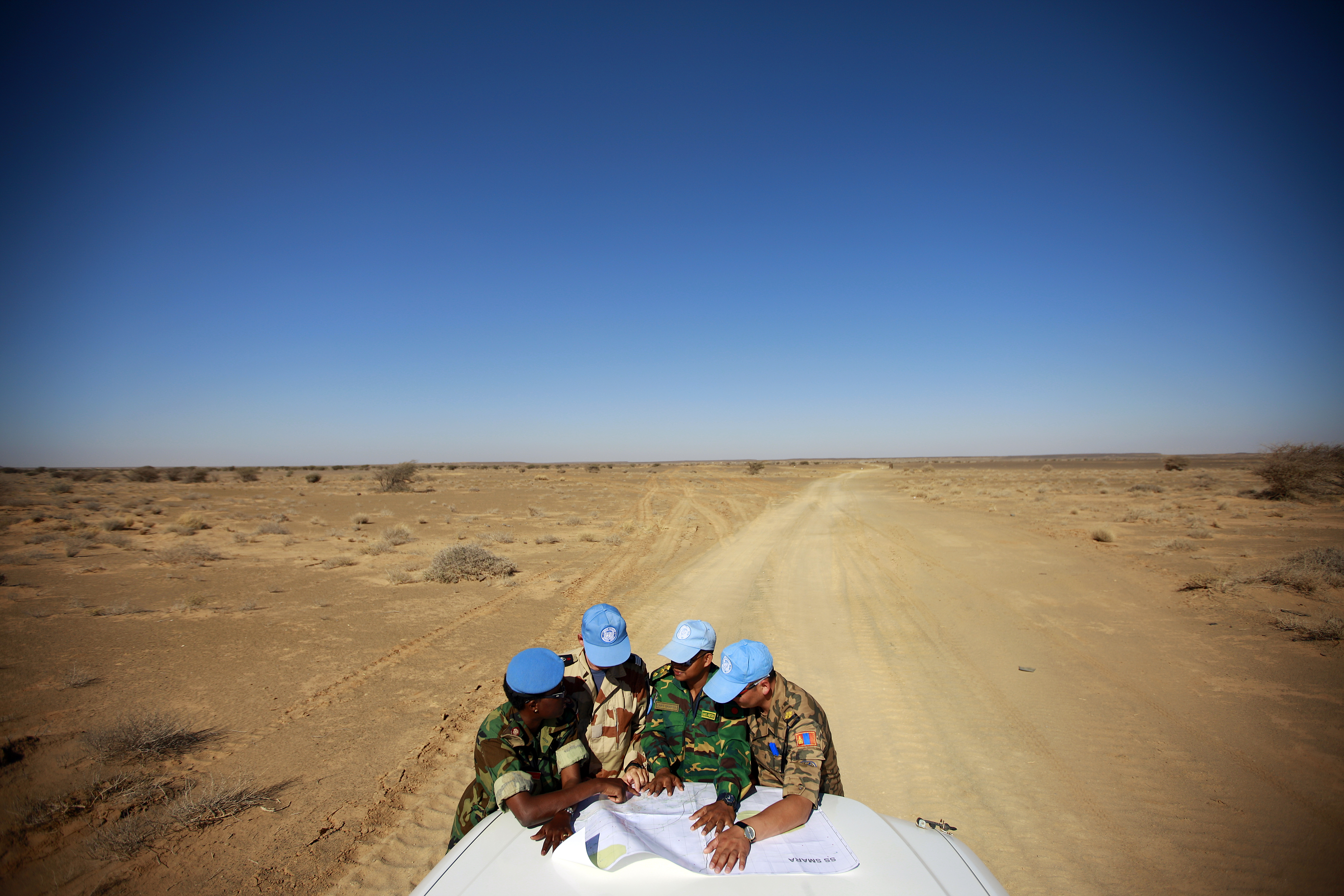

...The case of Western Sahara.

Article published by Dr. Juris (PhD) Hans Morten Haugen, University of Oslo in Law, Environment and Development Journal.

“The Right to Self-Determination and Natural Resources: The Case of Western Sahara"

Law, Environment and Development Journal (2007), p. 70, available at http://www.lead-journal.org/content/07070.pdf

By: Hans Morten Haugen, Dr. Juris (PhD) University of Oslo

Abstract: Phosphate, fish and possibly oil and gas all constitute important natural resources found on the territory and in the waters of Western Sahara. The importance of these natural resources must be recognized in order to understand the stalemate in the attempted process of decolonization from Morocco, going on for more than 30 years. The article analyses the ‘resource dimension’ of the right to self determination, as recognized in human rights treaties and in Resolution III of the UN Conference on the Law of the Seas, as well as several resolutions from the United Nations General Assembly. If the resources are exploited in a manner which does not benefit the peoples seeking to enjoy the right to self-determination, such exploitation is illegal. The article shows that the current exploitation takes place in a manner contrary to the interests of the local population, the Saharawis. The article also demonstrates that recent license agreements with Saharawi authorities in the field of oil and gas, signal a potentially new and constructive approach by international corporations.

Keywords: Conference on the Law of the Seas, European Union, Fisheries Partnership Agreement, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Morocco, oil exploration, phosphates, self determination, United Nations, Western Sahara.

Table of content:

1. The resource dimension of the right of peoples to self determination

2. The question of Western Sahara, particularly control over resources

3. The legal basis for preventing exploitation of the natural resources of Western Sahara

4. Phosphates

5. The EU-Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement

6. Do the oil and gas licenses point towards self determination for Western Sahara?

7. Conclusion

Self determination of peoples was recognized in the very first Article of the 1945 Charter of the United Nations, as a principle. Self determination hence is one of the four basic purposes the United Nations shall fulfill, on an equal footing with peace & security, human rights and (sustainable) development.

The right to self determination was recognized as a right in both the two central UN human rights treaties of 1966; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The most interesting part of Article 1, in which this right is recognized, is its paragraph 2:

All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit, and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.

This article will analyze the content and actual application of this human right of peoples. Of particular relevance is how this principle applies in the context of Western Sahara. It will also be analyzed whether other international treaties are relevant for understanding the scope of the right of peoples to dispose of their natural resources, including a prohibition against deprivation of a peoples own means of subsistence.

1. The resource dimension of the right of peoples to self determination

Article 1 of the two UN covenants sets out collective rights, which provides both a background against which the individual rights shall be understood, as well as serving as an important precondition for the exercise of the individual rights.(1)

An author understands that this paragraph constitutes an obligation on the States “to take measures to ensure that its own people are not in any case deprived of its own means of subsistence, including food […] and to investigate any situation where such deprivation is alleged to be occuring.” (2) Another author argues that the right to ownership of natural resources is absolutely crucial for the realization of the right to food. (3)

The wording of Article 1 is identical in the two 1966 Covenants, but their coverage must be considered to be a reflection of their different scope, with one covenant recognizing and regulating economic, social and cultural human rights, and the other civil and political rights, and to a certain extent also cultural rights, in the context of minorities. (4)

Article 1 has not been applied by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, but has been applied by the Human Rights Committee, in the context of rights of indigenous peoples. Moreover, the resource dimension of the right to self determination has recently been confirmed by the International Law Commission. (5)

It will be assessed what the terms ‘freely dispose’, ‘deprived of’ and ‘means of subsistence’ in fact imply. ‘Freely dispose’ does not mean that there can be an unrestricted use of the resource, but that the ecological concerns must be considered. The notion ‘deprived of’ relates to a situation in which forces outside the control of the community undermine the resource base. 'Means of subsistence' must include everything which is crucial in order to uphold life, of which food is an essential element. It is considered that the phrase ‘deprived of’ is of most relevance in this context of assessing the right of peoples to self determination, when resources are exploited against the will of the original inhabitants, as is the situation in Western Sahara.

Sepúlveda has found that there are two duties under the obligation to respect which relate to deprivation. The first duty is to avoid depriving individuals of the possibility to be self-supporting on the basis of their own work. The second duty is to abstain from depriving individuals of the means of subsistence, particularly their land. (6)

Among these authors writing in the field of human rights, there is hence an understanding of what the resource dimension of the right to self determination entails. These elaborations do not reflect positions expressed by States, however. One explanation for this is also that the body which is responsible for supervising the implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights does not bring up questions relating to Article 1 in their examination of State parties reports. This is unlike its sister committee, the Human Rights Committee, which does bring up issues relating to Article 1 in their sessions, with specific reference to indigenous peoples.

Insufficient enjoyment of peoples to the right to self determination, implying that the natural resources cannot be freely disposed of, can represent a serious impediment on the enjoyment of important human rights, such as the right to adequate food.

2. The question of Western Sahara, particularly control over resources

After being a Spanish colony (since 1885) and then province (since 1958), the process towards decolonization of Spanish Sahara was halted by the Moroccan invasion, taking place already in October 1975. The Green March was officially launched on November 6 the same year. The United Nations could not, despite its strong resolutions, prevent the Moroccan bombardment and forced eviction of more than half of the Saharawi population. This invasion took place in clear contradiction, and must be defined as an act of aggression.

Spain formally withdrew from the territories 26 February 1976. Spain however, according to the UN Under-Secretary-General on Legal Affairs, never did in a legal way "transfer sovereignty over the territory" (7) as this can only be done in accordance with the procedures set down by the United Nations. Hence, Spain is still the ‘administering power’ of Western Sahara. (8)

No other State has acknowledged Moroccos territorial control over overwhelming parts of Western Sahara. All legal evidences say that Morocco, by preventing the right of the people of Western Sahara to exercise their right to self determination in accordance with UN Resolution 1514, (9) acts in violation of international law.

Western Sahara is referred to as a so-called 'non-self-governing territories'. At the same time, Western Sahara is dealt with by the Fourth Committee of the UN General Assembly, which addresses matters relating to decolonization. The term occupied is not applied by the United Nations, but for all practical purposes, it is reasonable to hold that Western Sahara is under Moroccan military occupation. (10)

An occupation implies that certain provisions of the IV Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War would apply, in conformity with Article 6, which reads:

“…the Occupying Power shall be bound, for the duration of the occupation, to the extent that such Power exercises the functions of government in such territory, by the provisions of the following Articles of the present Convention: I to 12, 27, 29 to 34, 47, 49, 51, 52, 53, 59, 61 to 77, and 143.”

The most relevant of these provisions, in light of the Moroccan policy of encouraging Moroccan settlers, is Article 49.6, which reads: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.”

Moreover, the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States reads in paragraph 16.2: “No State has the right to promote or encourage investments that may constitute an obstacle to the liberation of a territory occupied by force.” (11) The Moroccan investments made particularly in and around Layoune for the purpose of facilitating exploitation of the natural resources must be considered to represent an obstacle to the liberation of a territory occupied by force. These investments contribute to integrating the economy of Western Sahara more strongly into the economy of Morocco, an integration which is considered to have "…potentially enormous implications for the Moroccan economy…" (12)

As this article builds on the premise that the United Nations formally considers Western Sahara to be a non-self-governing territory, the main basis of the argumentation will be taken from relevant legal material regulating such territories, even if it is correct to acknowledge that for all practical purposes, Western Sahara is occupied by Morocco.

The 2002 letter from the Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs to the Security Council lists several UN resolutions have been adopted concerning non-self-governing territories. (13) These resolutions neither prohibit resource exploitation or investments, if this is undertaken in collaboration with and according to the wishes of the peoples in these territories. The litmus test is if the economic activities are directed towards assisting these peoples in the exercise of the right of self-determination.

The territory and coast of Western Sahara has documented large amounts of two natural resources, phosphates and fish, as well as an undetermined amount of oil and gas: “The Maghreb is a region of strategic importance, not least for its abundant natural resources. Western Sahara may soon become an oil producer.” (14) To this list can also be added iron, uranium, titanium (15) and sand, which has actually been a large export article, in particular to the Canary Islands. (16) The amount and potential of each of these first three resources will be briefly assessed.

Phosphates: It is estimated that there are still enormous resources of phosphate, despite heavy extraction undertaken by both Spain and Morocco. (17) Western Sahara's shares of Moroccan-registered sales of phosphate imply that Western Sahara alone would be among the world's largest exporter of phosphates. Phosphate is important simply because it is non-substitutable.

Fish: The fish delivered in the occupied Western Sahara city of Laayoune alone represents 38,6 per cent of the total Moroccan reported fish catch. (18) Each year fishing vessels bring with them more than 1 million tones of fish from the seas that Morocco currently control, and which includes the coast outside of Western Sahara. (19)

Oil and gas: The amount of oil and gas on-shore and off-shore is still difficult to assess, but the fact that commercially viable amounts of oil and gas is presumed to exist, is considered to “…complicate any solution.” (20) A new situation emerged in 2006, however. Currently, all contracts with the Moroccan state oil company ONAREP are terminated, while eight companies entered in March 2006 into agreements with the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), granting them offshore oil and gas licenses in a total of nine license areas, six off-shore the coast of Western Sahara, and three on-shore. (21) The SADR has demarcated and announced bids for a total of 19 searching blocs. Currently, only parts of the on-shore license areas are currently under effective territorial control of the SADR, referred to as the 'liberated areas'.

There can be no doubt, therefore that these natural resources represent crucial economic assets for Western Sahara. As noted by one author: “…this conflict may be perceived as being essentially about natural resources and their exploitation by Morocco.” (22) This is confirmed by the CIA, which states: “Western Sahara depends on pastoral nomadism, fishing, and phosphate mining as the principal sources of income for the population.” (23) There has been considerable international attention devoted to the natural resources sought to be exploited by companies aligned with Morocco. (24)

3. The legal basis for preventing exploitation of the natural resources of Western Sahara

The basis for a legal assessment of how any administration of Western Sahara shall be conducted - including administration over natural - must start from the premise that Western Sahara is considered a non-self-governing territory - formally still administered by Spain. International law has two relevant legal provisions regulating non-self-governing territories.

First, Article 73 paragraph (b) of the UN Charter says that a UN member state which is responsible for “administration of territories whose peoples have not yet attained a full measure of self-government” shall “…develop self-government, to take due account of the political aspirations of the peoples, and to assist them in the progressive development of their free political institutions.”

In other words, the administering state shall administer the territories in a way that responds to the interest of the peoples in these territories, including their independent political interests.

Both Article 73 of the UN Charter and the subsequent resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly apply both the terms 'inhabitants', and ‘peoples’. These two are not necessarily the same, and it is the peoples, including indigenous peoples, who have the rights over the natural resources of a non-self-governing territory. Inhabitants is a wider category than peoples, and includes also those not originating from the territory. As stated in Article 73 of the UN Charter, the interests and well-being of all inhabitants in a non-self-governing territory are paramount. As made evident above, it is still Spain which is the administering power in Western Sahara, even if the administrative structures in place are set up by Morocco, which exercises effective control over most of the territory.

Moreover, neither Article 73 of the UN Charter nor the subsequent resolutions apply the term 'representatives'. This term is, however, used in the 2002 letter from the Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs. (25) This can be seen as a pragmatic approach, as it would be necessary to identify a body to relate to. The use of the term 'representatives' is, however, somewhat problematic. More specifically, how is the representative body established and identified as being the representative body?

In the specific context of Western Sahara, there can be no doubt that the identification with Polisario is very strong among the refugees in Algeria. For the Saharawis living in Western Sahara, there are clear indications that the support for Polisario is very strong also here, but the restrictions on any public expression of sympathy either with an independent Western Sahara or with Polisario, make any reliable accounts very difficult. Morocco has established its own political bodies in Western Sahara, which might currently represent the majority of the inhabitants in Western Sahara, as Moroccan settlers outnumber local Saharawis, and as there are Saharawis who are loyal to Morocco. However, these bodies cannot be said to represent the people of Western Sahara. In matters relating to natural resources, it is hence the only all-encompassing body for the Saharawis, namely Polisario, which must be consulted.

Second, Resolution III of the UN Conference on the Law of the Seas reads:

In the case of a territory whose people have not attained full independence or other self-governing status recognized by the United Nations, or a territory under colonial domination, provisions concerning rights and interests under the Convention shall be implemented for the benefit of the people of the territory with a view to promoting their well-being and development.

This resolution, which builds on Article 73 paragraph (b) of the UN Charter, emphasizes the economic interests of the peoples of the non-self-governing territory. If the activities related to natural resources undertaken by an administering power are done in accordance with the needs, interests and benefits of the peoples of that territory, and in consultation with these peoples or their representatives, the activities are not necessarily contrary to the UN Charter or Resolution III of the Conference of the Law of the Seas.

These two legal provisions apply both to fish and to off-shore oil and gas, but the Convention on the Law of the Seas obviously does not apply to on-shore resources, such as phosphates.

In this context, the human right of people to dispose of their own resources, with a particular emphasis on the ‘means of subsistence’, gives additional legal arguments. Hence, it can be stated that those resources which do fall under the scope of the Convention on the Law of the Seas, and are also ‘means of subsistence’ for a people, have a stronger protection against foreign exploitation than resources which are inland resources are do not represent such ‘means of subsistence’.

Are there any criteria to distinguish between resources which represent 'means of subsistence' and resources which do not? It must be argued that 'means of subsistence' cannot only refer to resources which are used for direct human intake. Also mineral resources which can be sold and generate financial resources, can represent means of subsistence. Without any income from such mineral resources, there will obviously be less possibilities to make investments in order to strengthen the subsistence base.

At the same time, the fish living along the long shore of Western Sahara represent a particularly important resource, which fall both with the ‘sea’ and the ‘human rights’ criteria. First, fish is a crucial nutritious resource. Second, fishing represents job opportunities for a population that no longer can rely only on nomadism. Third, the amount of fish available, and the vicinity to relevant markets, implies that the economic potential of fishing in the sea outside of Western Sahara is undisputed. At the same time it must be observed that fish has not traditionally been an important sector for the Saharawis.

After an analysis of the phosphates exploitation, which is the most known resource, the fisheries resources and then the petroleum resources will be analyzed. The analysis seeks to demonstrate that Moroccos economic motivations are at least equally important as the political motivations in keeping its control over the territory. (26)

4. Phosphates

With regard to phosphates, it was noted by the UN Mission visiting the then Spanish Sahara in May 1975: “…the territory will be among the largest exporters of phosphates in the world.” (27)

The phosphates were considered to be so important that the Madrid Agreement, (28) signed 14 November 1975 gave Spain 35 per cent of the shares in the Bou Craa phosphates mine, shares which Spain still holds. (29) The known reserves at Bou Craa are 132 million tons, and the annual production is around three million tons, (30) which makes it currently the third largest mine controlled by Morocco. The potential at Bou Craa, however, is far greater.

At the time of the signing of the Madrid Agreement, 70 per cent of Moroccos foreign currency income came from phosphates trade. (31) The Moroccan motivation for gaining control over the phosphates resources of Western Sahara were obvious, as Morocco by such control would be able to control world phosphates trade. Still, Morocco is the biggest phosphates exporter in the world.

The threat posed by Polisario against the mine itself and the conveyor belt initially closed down the production at Bou Craa, but these attacks have been less frequent after the completion of the sand wall through the territory in the mid-1980s, and the ceasefire in 1991. Still, however, the conveyor belt is subject to attacks, even if not all of these attacks can be traced back to Polisario.

The production at Bou Craa is shipped from Laayoune, and there have not been a lack of willing buyers. Even those that have regretted their specific purchase after being exposed in the media, do not categorically exclude that such purchase might happen again: “…we do not exclude that we will resume the trade after a new evaluation.” (32)

The phosphates trade from Western Sahara is hence taking place continuously, and high-ranking military officers play important roles in the phosphates extraction. Still it is Western Sahara's main natural resources. A proposal from the Western Sahara Resource Watch is that all governments simply must reject receiving such bulks of phosphates shipped from the port of Laayoune. (33)

Phosphates will continue to be a very important resource for the Western Sahara economy. Until now, however, the extraction of phosphates has been done in a way which adversely affects the interests of the people of Western Saharan, the Saharawis.

5. The EU-Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement

After passing through the Fisheries Committee and the plenary of the European Parliament, the Fisheries Ministers of the EU member states decided on May 22 2006 to enter into an agreement with Morocco, which applies to "the waters under the sovereignty or jurisdiction of the Kingdom of Morocco", giving 119 vessels, mostly Spanish, access to these waters.

The attempts to exclude the waters outside of Western Sahara from this Agreement hence were not successful. In the process leading up to the agreement, arguments presented by various representatives of the EU have been criticized for being less than convincing from an international law perspective. I will examine the various arguments and statements made.

EU Fisheries Commissioner Joseph Borg held in February 2006 that the agreement was “…in conformity with the legal opinion of the United Nations issued in January 2002." (34) This is not correct, as the author of this legal opinion, Hans Corell, himself stated in an interview following the EU decision: ”[the Swedish protests] is actually consistent with the opinion that I expressed in a statement that I made to the Security Council when I was the legal chief at the UN." (35)

The EU a month later issued a legal opinion which says that the Agreement would only be legal providing it was not …"carried out in disregard of the interests and of the wishes of the local population." The legal opinion states that it “…cannot be prejudged that Morocco will not comply with its obligations under international law vis-à-vis the people of Western Sahara.” (36)

This ignores the actual Moroccan policy until today. Very little indicates that Morocco is prepared to facilitate a fisheries policy which is defined and implemented together with and in accordance with the wishes of the legitimate representative of the Saharawian people. Moreover, the quoted paragraph does not spcify that it is only the former colonial people, the Saharawis, who has legal rights over the natural resources, while the current population, consisting to a large extent of Moroccan settlers, do not have such rights.

In very broad terms, Morocco has no other obligations vis-à-vis the people of Western Sahara than to stop all forms of aggression and to stop impeding a referendum on self-determination from taking place. The administering power is still Spain. Second, the political body representing the Saharawi people, who have traditionally inhabited Western Sahara, are strongly against the Agreement. (37) As most of the traditional inhabitants, are currently refugees, and as Saharawis represent only two per cent of those employed in fishing in Western Sahara, there is no likelihood that they will have any benefit from the Agreement.

It can be argued that the EU-Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement represents a de facto recognition of Morocco's continuing occupation of Western Sahara. EU enters into an agreement which covers also a territory over which Morocco has no legal status. This implies that Morocco has no competence to make any agreement with regard to resources found in Western Sahara. As stated by the Council on Ethics of the Norwegian Petroleum Fund: “Norwegian authorities have warned Norwegian companies against entering into economic activities in this area because such activities can be seen as support for the Moroccan sovereignty claims and thus weaken the UN sponsored peace process.” (38)

Moreover, the context for the signing of the agreement is one in which central European actors themselves have presented views which challenge the established and widely-shared view regarding Western Sahara. Spain, which has been the strongest advocate for the Agreement, has now a foreign affairs minister, Miguel A. Moratinos, who declares that Morocco is the administrative power, based on the 1975 Madrid Agreement. (39) As already argued, this Agreement does not transfer the authority over Western Sahara to Morocco. Moreover, the Agreement was entered into in breach of principles of decolonization as set down by the UN, as well as the 1975 Advisory Opinion on Western Sahara by the International Court of Justice.

Hence, from an international law perspective, and consonant with the general EU position regarding Western Sahara, there are two options. First, the Fisheries Agreement can be revised in order to only cover the water under the sovereignty of Morocco. Second, the Fisheries Agreement can be cancelled, as is it built on a wrongful premise that Morocco has legal competence to enter into an agreement which also covers a territory which Morocco occupies.

6. Do the oil and gas licenses point towards self determination for Western Sahara?

As a contrast to the EU-Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement, the agreements entered into between eight different oil companies and the Government of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic is based on an acknowledgement that the resources of Western Sahara shall not be exploited unless this is for the direct benefit for the Saharawi people, in accordance with the positions of their representative body, which is Polisario.

There has been a long history of several petroleum companies interest in exploring oil resources in and off Western Sahara, (40) but this interest did not materialize in specific contracts until the (now cancelled) 2001 contracts between the Moroccan Oil Company ONHYM and KerrMcGee and Total, respectively, and then the contract of 2002 between SADR (Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic)(41) and Fusion Oil&Gas. (42)

A real change, however, happened in the first months of 2006, with the termination of the contract with KerrMcGee. Later in the year, however, two new contracts were signed. New contracts have been entered between Moroccan authorities. (43) March 2006 also saw the signing of contracts between SADR and no less than eight international oil companies. These latter contracts have a clause saying that oil exploitation is on hold, awaiting a solution to the conflict.

As stated by the UK-based EnCore Oil: "No exploitation of the Western Sahara offshore resources will be undertaken by EnCore until such time as the current dispute has been resolved." (44) Another company which has entered into an agreement with the Government of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic applies the terms “…successful resolution to the sovereignty of the territory…” (45)

These clarifications represent challenges to the Moroccan government and its state oil company ONHYM, also as they took place as the last company Kerr-McGee decided not to renew its contracts with ONHYM. By stressing that expoitation of resources from the territories or shores of Western Sahara shall be undertaken only after the conflict has found a solution, the oil companies must be considered in accordance with international law, as expressed by the UN Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs. (46)

At the same time, the presentations given by the oil companies are not fully in compliance with a precise understanding of the territories. As an example, Europa Oil and Gas uses the phrase “…territory currently governed by Morocco…” (47) While this is not an accurate formulation, it does not equate the wrongful formulations by central EU officials, stating that Morocco is the administering power of the non-self-governing territory of Western Sahara.

The oil and gas agreement are important in three ways. First, they are entered into with the political representatives of the Saharawian people. Second, they are formulated in a way that recognizes that the Saharawians are the rightful people to take all decisions regarding the exploitation of resources in the territories. Third, they are formulated in a way that makes it implicit that a solution over the territories will be found.

At the same time, it is not necessarily clear what an acceptable solution implies. To "resolve a dispute" might be different from the achieving successfully a “resolution of the sovereignty of the territory". The latter phrase must be considered to be more ambitious than the former. The first company to enter into an agreement with the SADR, Fusion Oil & Gas, has stated explicitly that they fully expect "…a just resolution that allows the Saharawi people to control its own territory…” (48) Such a formulation is more direct than the eight companies entering into contracts with SADR in 2006, but also these contracts point in the same direction.

7. Conclusion

We see that there are different scenarios for the control over resources, depending on whether one considers the situation in the field of fishing or in the field of oil and gas. The legal facts are the same, as both of these resources are to be regulated in accordance with Resolution III of the UN Conference of the Law of the Seas. Moreover, the Western Saharan population can make human rights-based claims, as there is a prohibition to deprive a people of its own means of subsistence.

The solutions are in principle very easy. First, the EU should revise its Fisheries Partnership Agreement with Morocco, in order to exclude Western Sahara from its scope. This is exactly what is done in the 2004 US-Morocco Free Trade Agreement. (49) It should be no more difficult for the EU.

Second, international pressure should be exercised on Morocco to get a Moroccan approval and loyal implementation of the widely recognized peace plan as set out in the so-called ‘Baker II’. (50)

Third, while awaiting a solution to the conflict over the Western Sahara territory, in accordance with principles of international law, as well as Security Council Resolution 1495, there should be no involvement in resource exploitation from the territory or water of Western Sahara by any companies. (51) Such exploitation is predetermined to take place without the approval of the representatives of the population inhabiting this territory, namely the Saharawis.

It is particularly worrying that the EU is legitimizing the exploitation of the fishery resources outside the coast of Western Sahara, and that this effort is led by Spain, which bears a considerable responsibility for the tragedy of the Saharawis. The arguments presented by the EU in the process of entering into the Fisheries Agreement are less than convincing, and represent real threats against the achievement of a just and lasting peace for the territory of Western Sahara and an end to the suffering of the Saharawis, both the refugees and those living in the occupied territories.

The oil and gas agreement, on the other hand, represent important steps forwards for the recognition of the Saharawis as the people who should rightfully be in control over its natural resources.

Footnotes:

(1) The Human Rights Committee has issued a General Comment on Article 1, in which the Committee states: "The right of self-determination is of particular importance because its realization is an essential condition for the effective guarantee and observance of individual human rights and for the promotion and strengthening of those rights." (General Comment 12 on Article 1, paragraph 1).

(2) Philip Alston, “International Law and the Human Right to Food”, in P. Alston and K. Tomasevski eds.: The Right to Food, 9, 40 (Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1984).

(3) Jan Hancock, Environmental Human Rights: Power, ethics and law (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2003). He considers the right to ownership of resources as an ‘environmental human right’ found to be necessary for the realization of the other human rights.

(4) Article 27 on the rights of minorities reads: In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, or to use their own language.

(5) The International Law Commission referred to the final sentence of Article 1.2 in the context of defining which countermeasures shall not affect States' obligations; see UN doc A/56/10, General Assembly Official Record, Fifty-sixth Session, Supplement No. 10, 336 (United Nations 2001).

(6) Magdalena Sepúlveda, The Nature of the Obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 212-214 (Antwerpen, Oxford, New York: Intersentia, 2003).

(7) S/2002/161 (Letter dated 29 January 2002 from the Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs, the Legal Counsel, addressed to the President of the Security Council), paragraph 6; at http://www.arso.org/UNlegaladv.htm.

(8) On the distinction between ‘administering power’ and ‘administrative power’, see Carlos R. Miguel, "Los Acuerdos de Madrid, inmorales, illegales y políticamente suicidas"; at: http://www.gees.org/articulo/2344.

(9) UN Resolution 1514 (XV) “Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples” reads in paragraph 5: "Immediate steps shall be taken, in Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories or all other territories which have not yet attained independence, to transfer all powers to the peoples of those territories, without any conditions or reservations, in accordance with their freely expressed will and desire, without any distinction as to race, creed or colour, in order to enable them to enjoy complete independence and freedom."

(10) General Assembly Resolution 34/37 of 1979 ("Question of Western Sahara") paragraph 5 reads: "Deeply deplores the aggravation of the situation resulting from the continued occupation of Western Sahara by Morocco", while paragraph 6 calls upon Morocco to "...terminate the occupation of the territory of Western Sahara".

(11) UN General Assembly Resolution 3281 (XXIX) of 1974.

(12) Toby Shelley, Endgame in Western Sahara: What Future for Africa's Last Colony? 36 (London: Zed Books, 2004).

(13) See footnote 7 above, paragraphs 10-12.

(14) Francesco Bastagli, “The forgotten referendum”, International Herald Tribune 24 November 2006, at: http://www.iht.com/articles/2006/11/24/opinion/edbastagli.php. Bastagli served as Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Western Sahara 2005-06.

(15) See Shelley, footnote 12 above, 78-9, observing that these are strategic and non-substitutable resources.

(16) Ibid, 79, finding that the volumes in 2001 were 754,579 tons of sand.

(17) Morocco, which illegally exploits Western Sahara's phosphate resources, is the world's leading exporter of phosphate. Morocco and Western Sahara together keep more than 50 per cent of the world's phosphate reserves and more than 60 per cent of the world's reserve base, according to the US Geological Survey; at http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/phosphate_rock/phospmcs96.pdf. See also http://www.sei.se/dload/2004/Rosemarin_NP.pdf.

(18) 2004 figures from Briefing: EU-Morocco Fisheries Partnership Agreement: Why Western Sahara should be excluded; Briefing prepared by War on Want and Western Sahara Resource Watch February 2006, at: http://www.fishelsewhere.org/documents/Legal%20breifing%20for%20Europe.doc.

(19) Eurofish March / April 2003: “Morocco: Modernization programme for the fish industry”, at: http://www.eurofish.dk/?id=1501&groupId=2.

(20) Erik Jensen, Western Sahara: Anatomy of a Stalemate, International Peace Academy Occasional Paper Series 120 (Boulder, Co.: Lynne Rienner Publishers 2005).

(21) SADR Petroleum Authority Press Release 17 March 2006: SADR Offshore Oil & Gas License Awards:

Successful Conclusion of the 2005 Western Sahara Licensing Oil and Gas Initiative, at: http://www.arso.org/sadroilandgas170306.htm.

(22) Raphael Fisera, People vs. Corporations? Self-determination, Natural Resources and Transnational Corporations in Western Sahara, 10 (M.A.Thesis, European Inter-University Centre for Human Rights and Democratisation, Venice and University of Deusto, Bilbao, 2005) at: http://www.arso.org/WSthesisFi.pdf.

(23) The World Factbook: Western Sahara; at: https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/wi.html.

(24) Toby Shelley, "Natural Resources and the Western Sahara", in C. Olsson ed: The Western Sahara Conflict The Role of Natural Resources in Decolonization, Current African Issues No. 33 17 (Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 2006).

(25) See footnote 7, paragraph 24.

(26) See Shelley, footnote 12, 61-80; see also Richard Knight, The Reagan Administration and the Struggle for Self-Determination in Western Sahara, paper written for the American Committee on Africa 1991; http://richardknight.homestead.com/files/wsreagan.htm; and Fisera, footnote 22 above.

(27) UN doc. A/10023/Rev.1 (1975): Report of the UN Visiting Mission to Spanish Sahara, 81.

(28) The Madrid Agreement, which divided the territory of Western Sahara between Morocco and Mauretania (withdrew in 1979), while Spain kept certain economic interests, is contrary both to UNGA Resolution 1514 (XV) from 1960 ("Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples"), the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice of 16 October 1975, and a number of specific UN resolutions.

(29) For a more comprehensive analysis of the phosphates industry at Bou Craa, see France Libertés-AFASPA [Association Française d'Amitié et de Solidarité avec les Peuples d'Afrique] Report: International Mission of Investigation in Western Sahara 28 October to 5 November 2002; http://www.arso.org/FL101102e.pdf.

(30) Shelley, footnote 12, 70-1.

(31) Ibid, 72; see also Tony Hodges, Western Sahara: The Roots of a Desert War 174 (Westport, Ct.: Lawrence Hill, 1983).

(32) "Yara admits dubious phosphate trade", in Dagens Naeringsliv (Norway), 7 July 2005; at http://www.newsfeeds.com/archive/soc-culture-algeria/msg01810.html.

(33) See “New Zealand's Phosphate Trade With Western Sahara And Why It Is Wrong” (Rod Donald, Green Party Trade Spokesperson, 28th July 2005), where the following arguments are given http://www.greens.org.nz/searchdocs/other9018.html:

- participating in the pillage of Western Sahara;

- assisting in financing the illegal Moroccan occupation;

- giving legitimacy to this occupation.

(34) Quoted in press release of 29 May 2006: “New EU - Morocco fisheries agreement in breach of international law”; see: http://www.fishsec.org/article.asp?CategoryID=1&ContextID=13. For the legal opinion, see footnote 7.

(35) EU accepted agreement in occupied waters: Interview with the UNs former legal chief, Hans Corell, Swedish Radio 22 May 2006, at: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Sahara-Update/message/1758.

(36) Legal Service in European Parliament: "Legal opinion: Proposal for a Council Regulation on the conclusion of the Fisheries Partnership Agreement between the European Community and the Kingdom of Morocco - Compatibility with the principles of international law", SJ-0085/06, 20 February 2006.

(37) See 22 May 2006 "Polisario statement regarding EU-Morocco fisheries agreement" at: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Sahara-Update/message/1757, where Mohamed Sidati, Polisario Minister Delegate for Europe refers to the Fisheries Agreement as a “very grave blunder”.

(38) "Recommendation on Exclusion from the Government Petroleum Fund's Investment Universe of the Company Kerr-McGee Corporation", at: http://odin.dep.no/etikkradet/english/documents/099001-230017/dok-bn.html.

(39) References can be found in Miguel (2006), footnote 8 above.

(40) See Anthony G. Pazzanita: Historical Dictionary of Western Sahara (3rd ed.) 340-44 (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press 2006); see also Fisera, footnote 22 above, 47; and Shelley; footnote 12 above, 65-66.

(41) The SADR was declared on 28 February 1976, after the last Spanish military presence had left. The Republic is a member of the African Union (AU), and the President of the SADR, Muhammed Abdelaziz, is also Vice-President of the AU.

(42) Fisera, footnote 22 above, 52-53.

(43) The two contracts were signed in May 2006 between ONHYM og Kosmos Energy; see: http://www.vest-sahara.no/files/pdf/onhym_agreements_2006.pdf and in December 2006 between the Moroccan company San Leon and GB Oil and Gas Ventures Limited (30%) / Island Oil & Gas plc (20%), respectively; see: http://www.islandoilandgas.com/default.asp?docId=12442&newsItem=12760.

(44) See Encore Oil:"Western Sahara" at: http://www.encoreoil.co.uk/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=53.

(45) See Europa Oil &Gas: “Operations in Western Sahara”, at: http://europaoil.co.uk/.

(46) See footnote 7 above.

(47) See footnote 45 above.

(48) PESA News April/May 2003: Fusion provides 200,000 km2 study for new African acreage chance; at: http://www.pesa.com.au/Publications/pesa_news/april_03/sahara.htm.

(49) See letter from US Trade Representative, Robert Zoelick of 20 July 2004 at: http://www.house.gov/pitts/temporary/040719l-ustr-moroccoFTA.pdf.

(50) The Peace plan for self-determination of the people of Western Sahara (Baker II) is included as Annex II to Report S/2003/565 of the UN Secretary-General to the Security Council. The Security Council adopted the plan unanimously by Security Council Resolution 1495 of 31 July 2003, which states in paragraph 1: “…support strongly the efforts of the Secretary-General and his Personal Envoy and similarly supports their Peace plan for self-determination of the people of Western Sahara…”

(51) For a conclusion that the plunder of the natural resources “…benefit only a few individuals”, see France Libertés/AFASPA, footnote 29 above, 36.

Order our Western Sahara poster!

“Try to Visit Western Sahara”…

The Security Council fails Western Sahara and international law

On 31 October 2025, a new resolution was adopted in the UN Security Council calling on the Saharawis to negotiate a solution that would entail their incorporation into the occupying power, Morocco.

Saharawis Demonstrate Against Trump Proposal

The United States has proposed in a meeting of the UN Security Council on Thursday that the occupied Western Sahara be incorporated into Morocco.

Skretting Turkey misled about sustainability

Dutch-Norwegian fish feed giant admits using conflict fishmeal from occupied Western Sahara. Last month, it removed a fake sustainability claim from its website.