"Two of my friends were arrested because of me. Not that I had known them for a long time. But it was because we were together they were arrested." By Thomas Frantsvold, Rafto Foundation.

By Thomas Frantsvold,

The Thorolf Rafto Foundation for Human Rights.

published in Norwegian daily Bergens Tidende, 19.01.2007 (Norwegian) and on Rafto Foundation homepages (English).

What happened in Norway and large parts of Europe during WWII, is happening today in Western Sahara, which has been occupied by its Northern neighbour, Morocco. My two friends, who I had met just a few hours earlier, are Sahrawis, and therefore second-class citizens in their own country. To try and protect them from further harassment, I will not mention their names here. They were arrested while, and because, they were walking with a foreigner on the main street of Dakhla, the second largest city of Western Sahara and an important harbour for the Moroccan fishing fleet.

And that is what this is all about. Dakhla doesn't harbour Western Sahara's fishing fleet, but Morocco's. Western Sahara is exploited by the Moroccan occupation forces, which sell the fish phosphate and other minerals of Western Sahara, and prepare to exploit and sell its petroleum.Western Sahara is somewhat larger than Great Britain, but sparsely populated. And the number of Moroccan settlers and security forces are many times higher than the Sahrawis currently living in the occupied areas. The Moroccans have been seduced by low taxes, high salaries work and welfare programmes. Most Sahrawis live in refugee camps in Algeria.

"The suppression continues. Nobody is allowed to freely express their opinions. People are beaten every day. A former prisoner was thrown into jail again yesterday", Sidi Mohammed Daddach told me in El Aaiun, the capitol of Western Sahara last December. He was awarded the Rafto Prize for Human Rights in 2002, for his and his people's long fight for human rights and self-determination. "There are Moroccan police and soldiers on every corner, and they imprison people for carrying the Sahrawi flag. Despite that, it has become more common to carry the flag, even though they are arrested and tortured", he said. After torture and 24 years of confinement in Morocco's prisons, Daddach knows what he is talking about.

Despite the close surveillance, common imprisonments, threats and torture, the opposition to the occupation is growing. Sahrawis are staging protests all over Western Sahara, and analysts say the activists inside the occupied areas have now taken over the fight from the exile-movement in Algeria.

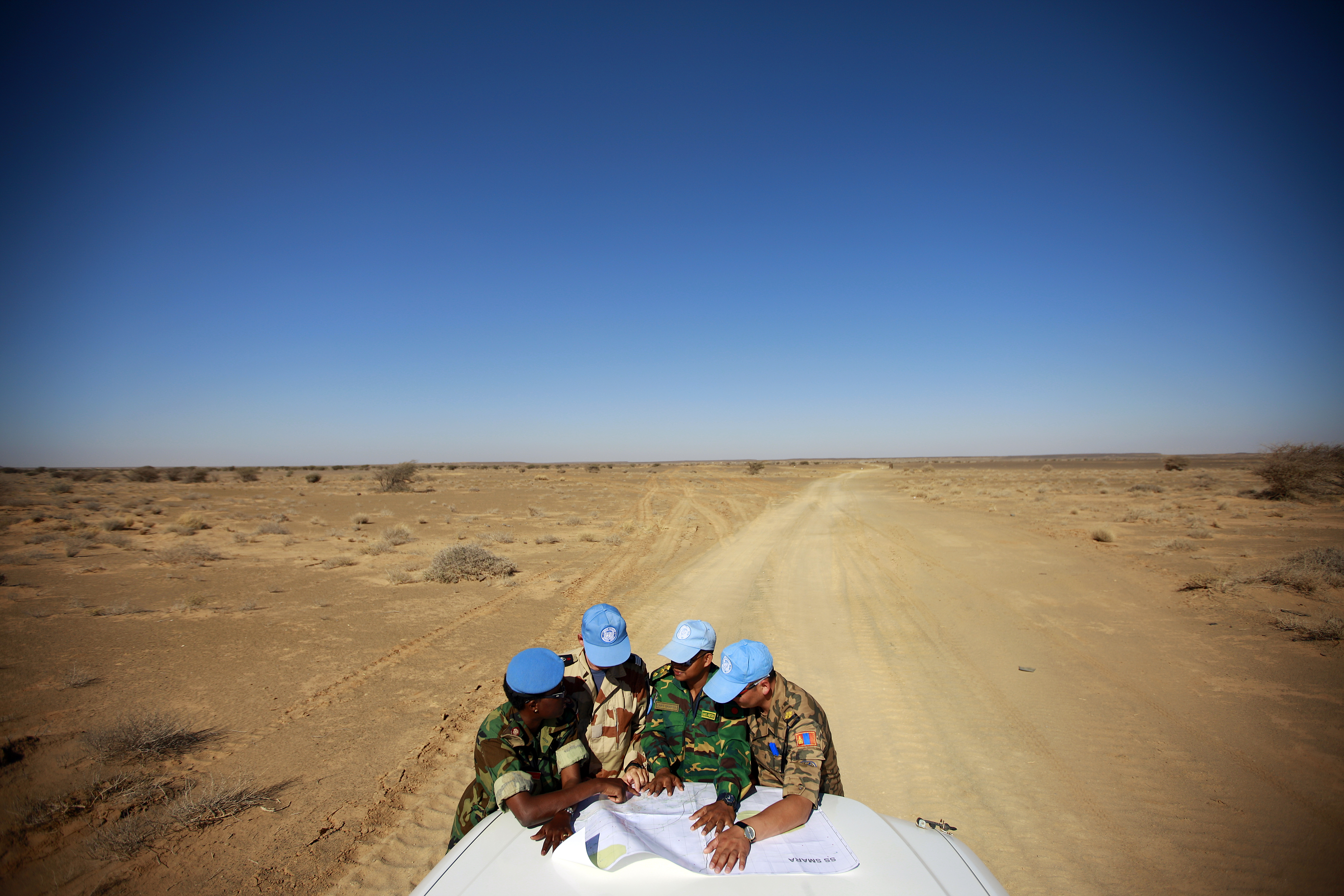

Morocco and Front Polisario signed an agreement in 1988, having spent the time since the Spanish withdrawal in 1976 fighting. The UN Security Council supported the parties in 1991, and took responsibility for organising a referendum to decide over the future of Western Sahara. Since then, not much has happened. A UN force is still stationed there, overseeing a truce. The situation seems dead-locked.

Morocco claims that the referendum as a solution to the conflict has expired on date, and will no longer accept anything else than Western Sahara as a part of Morocco. Polisario has surprisingly accepted that all Moroccan settlers living in Western Sahara since 1999 can vote in a referendum. Morocco opposes even that, and the UN has not been able to put enough pressure on the parties to reach a solution, particularly on Morocco.

According to the UN, the Western Sahara is a non-self-governing territory, and the Security Council has condemned the Moroccan occupation and acknowledged the Sahrawis right to self-determination a number of times.

One would think the international community would fight more for adherence of international law, especially this close to Europe's doorstep.

But even when that notion is set aside, there are many parts the European and International community can play. Indeed, we should demand that our governments stand up for human rights, and fight occupation and injustice in the occupied territories of Western Sahara.

Sahrawi activists and politicians are object to arbitrary prosecution, torture and threats, and many of them live under distressing conditions in Moroccan jails. European political interests are not served well by staying silent, nor are our economic interests. At the same time it is unfortunate and discomforting that Morocco is able to deter diplomats, journalists and others from visiting Western Sahara, in an effort to try and hide the suppression, harassment and surveillance. The arrest of Swedish journalist Lars Björk February 19 2007, proves a case in point.

Just before my friends were taken away by police, we had a few seconds alone. With tears choking in their throats, they assured me "everything would be ok. And we shared a warm and extra firm hand-shake.

Half an hour earlier, one of the Sahrawis gave me this letter:

"We have been invaded, and are under occupation. They are killing our people, stealing our fish and oil, and do us injustice. My only wish is for us to return to our cities. Can I ask you to help?

Order our Western Sahara poster!

“Try to Visit Western Sahara”…

The Security Council fails Western Sahara and international law

On 31 October 2025, a new resolution was adopted in the UN Security Council calling on the Saharawis to negotiate a solution that would entail their incorporation into the occupying power, Morocco.

Saharawis Demonstrate Against Trump Proposal

The United States has proposed in a meeting of the UN Security Council on Thursday that the occupied Western Sahara be incorporated into Morocco.

Skretting Turkey misled about sustainability

Dutch-Norwegian fish feed giant admits using conflict fishmeal from occupied Western Sahara. Last month, it removed a fake sustainability claim from its website.