Op-ed by Thor Richard Isaksen, Leader of the Students' Peace Prize, and Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Committee Member, and former chairman of the Nobel Peace Prize committee, the Students' Peace Prize, 2009.

Published in Dagbladet

27 February 2009

Original version (Norwegian)

The Students' Peace Prize for 2009 goes to a 23-year-old female student from Western Sahara. The Prize focuses on a conflict the West seems to have forgotten and on a student commitment that is all too infrequently recognised.

Elkouria Amidane is a student activist and human rights advocate. She is being awarded the Students' Peace Prize for her work for Sahrawi students and for a peaceful solution of the conflict in Western Sahara. Amidane is only one of many young Sahrawis who are involved in this struggle, which is mostly fought in silence.

This year's winner has the support of all of Norway's students and of all political youth parties. When the Peace Prize winner was in Norway in 2007, she contributed to the creation of agreement across party lines with regard to Western Sahara's right to independence. By means of youth parties and student organisations, the future leaders of Norway have expressed their support of Amidane, but where is the support of today's rulers? Why isn't the Norwegian government on the field?

Western Sahara, an area on the northwest coast of the African continent, suffers under a Moroccan occupation that is contrary to international law. After the colonial power Spain withdrew from the country in 1976, the territory was by agreement divided in two between Morocco and Mauretania. The agreement was entered into in secret, and both Spain and Mauretania have later withdrawn from it. Furthermore, the agreement has been declared illegitimate and illegal by the UN.

The resistance movement in Western Sahara managed by means of armed struggle to force Mauretania out in 1979, but Morocco still retains its occupation. The armed struggle against the occupying power ended, however, in 1991. A truce was declared; in addition to this, it was agreed that the UN would organise a referendum. This was to decide whether Western Sahara was to be independent or be annexed by Morocco.

Almost 20 years later the referendum has not yet been held. Up until 2004 the referendum was delayed because of disagreement about the voting rights regulations, but since 2004 Morocco has refused point-blank to respect the agreements entered into and permit the referendum in Western Sahara. About 80 nations have recognised Western Sahara as an independent country, and no nation has formally recognised Morocco's claim to the area.

But Norwegian authorities have, together with most other Western countries, remained silent. This makes it possible for Norwegian businesses to drain occupied Western Sahara of resources through agreements with Moroccan authorities. One example is the seismic company Fugro-Geoteam, which, according to Norwatch, as late as January this year was involved in oil exploration off the coast of Western Sahara, on assignment from Moroccan authorities. Despite the fact that this is in conflict with advice from the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the reactions against such activity are all too weak.

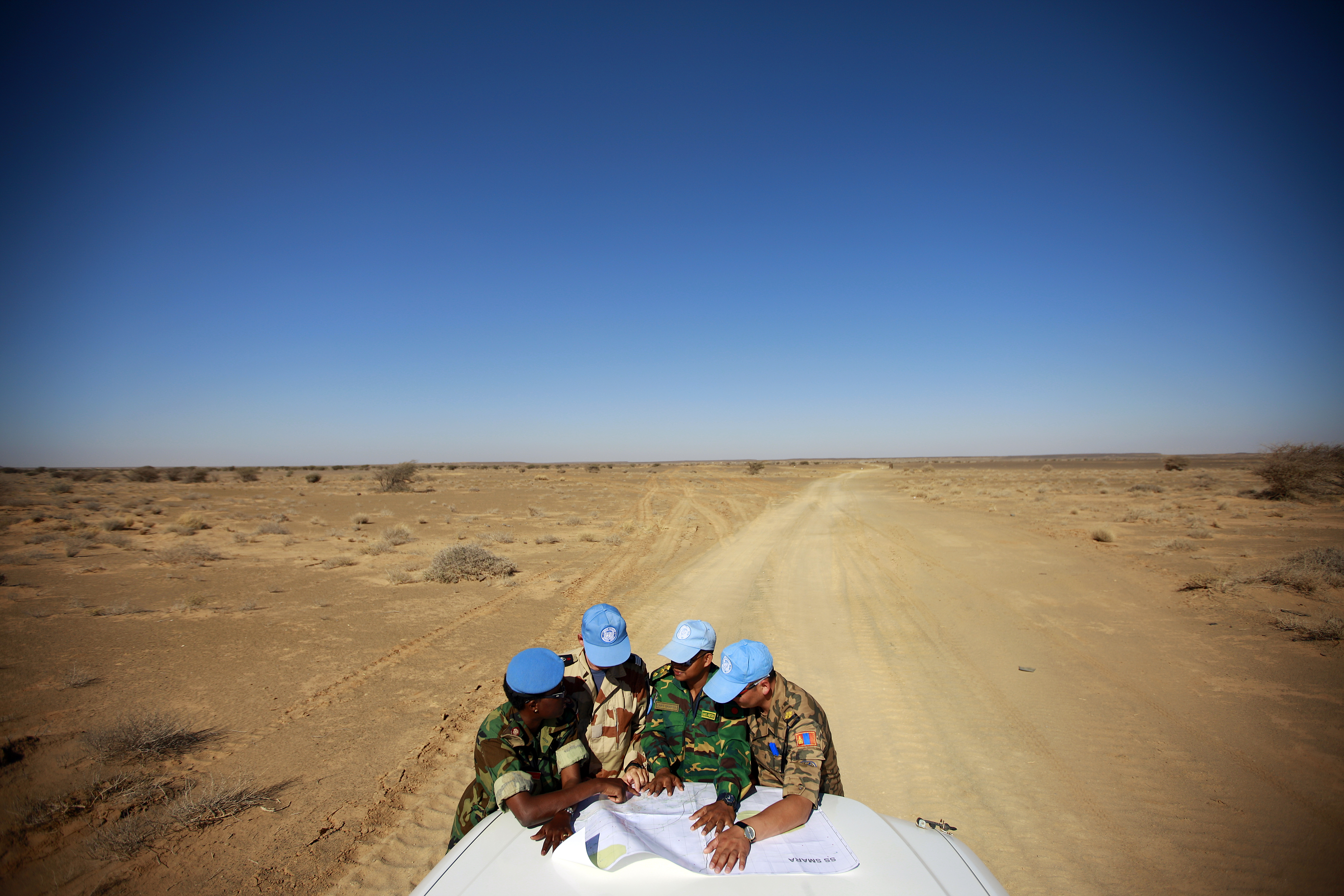

The Sahrawis, the local population of Western Sahara, is daily exposed to great suffering while the international community straddles the fence. The situation is deadlocked, and almost half of the population lives in absolute destitution as refugees. Since 1980 Western Sahara has been split in two by a 2200-km-long mine-covered defence wall built by Morocco. The left side, a resource-rich area under Moroccan control, contains all the big cities and settlements. The east is the complete opposite: a desert landscape deficient in resources and partly mine-covered, where 170,000 refugees are prevented from having contact with the Sahrawis on the west side.

Moroccan authorities have not established universities or other institutions of higher education in Western Sahara, so the few Sahrawi young people who are permitted to study must go to Morocco. The Moroccan authorities clamp down on political involvement, and the threshold for being thrown out of school is low. This entails that few Sahrawi students dare to get involved. Peace Prize winner Amidane was, for example, thrown out of school for having criticised the Moroccan king. The manners of today's student activists are not the same as those used by the 1968 generation.

Amidane utilises new methods and works purposefully to document and make visible infringements through videos, among other means. Internet-based information channels such as YouTube represent new possibilities, a new set of measures, and a much larger audience. This also entails that the activists' risks increase considerably. This new manner of distribution may be described as a double-edged sword, by means of which both the profits and the risks are increased for all parties involved. During a demonstration at the University of Marrakesh in 2008 the Moroccan police attacked both Moroccan and Sahrawi students with tear gas and violence. Amidane filmed the incident and spread it on Internet. She has since received anonymous telephone warnings that threaten her with the use of violence or kidnapping if she moves around outdoors.

Despite her peaceful methods, Amidane has, like many other human rights advocates in Western Sahara, experienced abuse and torture. As young, as a student and as a woman she encounters discrimination. All the more important, and more impressive, is her struggle. She continues to put pressure on Moroccan authorities, and it is this courage that makes her this years winner of the Students Peace Prize. In being awarded the Students' Peace Prize, Amidane not only receives a sum of money and physical evidence of the prize. She also receives support and a promise of follow-up in future years.

The Students Peace Prize is not a prize that ensures a middle-aged peace expert a mention in the history books. It is a prize that goes to those who know the struggle for peace and justice personally, to those who fight at the risk of their lives for a better future. For ten years the Students' Peace Prize has focused on the fate of brave students like Amidane. Today she will come to The International Student Festival in Trondheim (ISFiT), Norway, to receive the tribute of the gathered students of Norway.

Translated to English by the Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara.

Order our Western Sahara poster!

“Try to Visit Western Sahara”…

The Security Council fails Western Sahara and international law

On 31 October 2025, a new resolution was adopted in the UN Security Council calling on the Saharawis to negotiate a solution that would entail their incorporation into the occupying power, Morocco.

Saharawis Demonstrate Against Trump Proposal

The United States has proposed in a meeting of the UN Security Council on Thursday that the occupied Western Sahara be incorporated into Morocco.

Skretting Turkey misled about sustainability

Dutch-Norwegian fish feed giant admits using conflict fishmeal from occupied Western Sahara. Last month, it removed a fake sustainability claim from its website.